“What is your favorite film genre?“ is a very difficult question. I love space operas, satires, road movies, war films and so much more. If I had to name just one or two, I would pick the ones that stand for cinema like no other in my opinion. Mob films – and Wild West movies.

Be it the classics of Howard Hawks and John Ford or the gritty, brutal spaghetti westerns of the 1960s. They brought us cool, taciturn heroes (and anti-heroes), memorable gunfights and showdowns and timeless scores that make me get goosebumps every time.

Yet the most important aspect of westerns, in my opinion, is the philosophical questions they pose. Let me explain how I define this genre. There are two types of genres: those determining the setting and those determining the tone. Examples for the first one are science fiction, history, crime and so on. The second category includes genres like action, drama or comedy.

At first sight, one might claim that westerns are a setting-defined genre. When we watch this type of movie we can be sure to see cowboy hats, horses, gallows, deserts, and gun slinging badasses. But taking a closer look, we will see this type of movie is dictating more than the setting. Many westerns share similar storytelling tropes and general atmosphere.

And while there are films like Kevin Costner’s “Dances with Wolves” that play in the Wild West, but do not tell a typical western story, there are also some with a western tone that is set somewhere else in the world or at another time. A pioneer of this kind of movies is Akira Kurosawa.

His famous samurai epics “Seven Samurai” and “Yojimbo” were inspired by the works of Ford and Hawks and for their part were remade in a Wild West setting (“Seven Samurai” became “The Magnificent Seven”, while “Yojimbo” was the blueprint for even two classics, “Fistful of Dollars” and “Django”). Quentin Tarantino has also contributed to this specific genre of “non-setting westerns” with “Kill Bill” and “Inglourious Basterds”.

What makes them westerns? Let’s analyse their plots. “Seven Samurai” tells the story of a poor village whose inhabitants recruit mercenaries to defend them against bandits ravaging the countryside. “Kill Bill” is about the campaign of revenge of a woman attempted to be killed by her ex-lover. “Inglourious Basterds” features a group of American Jews killing Germans soldiers in Nazi-occupied France.

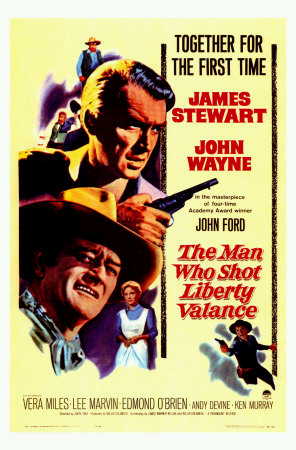

They all have one thing in common: their protagonists are seeking justice in an environment failing to provide this justice, often because it is lawless. This grounding makes many of these movies a philosophical discourse on justice and vigilantism. A film that discusses these topics like no other is John Ford’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”.

It is an intriguing drama about media, politics, and society. Thrilling and funny, it features well-written characters acting out a well-written story. Ransom Stoddard (John Wayne) is an idealistic lawyer from the East Coast who gets ambushed by the outlaw gang of Liberty Valance on his way west. He is beaten up and left in the middle of nowhere.

Gunslinger Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) saves Stoddard and brings him to the village of Shinbone. This is followed by a conflict between the two about how to deal with the desperado Valance. They represent opposite philosophies: Doniphon is a good-hearted, yet prone to violence anarchist, Stoddard a dedicated republican firmly believing in the law. While one sees guns as the only solution to the threat of Valance, the other wants to put him in jail.

In Shinbone, Stoddard finds himself in another universe where barely anyone can read or write and bad guys can only be stopped by guns. He starts teaching the citizens from young to old and initiates discussions about statehood. Doniphon, in the meantime, feels at ease with the open range life. He values loyalty, honesty and informal rules over the law — to threats he will answer with gunfire.

John Ford doesn’t judge about which of his characters is right. He lets their views collide and leaves the decision up to the audience. Yet when Shinbone decides for statehood, in the end, we feel a slight regret about this end of the era when cowboys like Doniphon ruled the Old West.

“The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” is an excellent examination of the tension between law and liberty. To get an idea of how these two values affect each other you have to watch this piece. And while the picture this film is painting, is romanticised, it invites one to dream about the way of life in a society not ruled by a government but by voluntary agreements between honest people.

I think it is a perfect example of what this genre is about. It’s not about horses and guns in the first place, but about the question of how to organise our society to fight and prevent evil. This question is an important one and it still will be in the future. Wild West movies tackle this question in the most direct way — that’s why we need more of them.

Picture: Wiki

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, click here to submit a guest post