If this article has caught your attention, you might be concerned about the author’s mental health – and you would not be entirely wrong. Nevertheless, I hope that, by the time you have finished reading, this concern will be accompanied by a sense of awakening – or perhaps even a touch of nausea. Once again, you may come to see how we are all, to some extent, captives of a one-sided narrative, even though our constitutions proudly proclaim “freedom of thought” and “freedom of information.”

Since we were kids, the majority of us – speaking as a “western” kid – were taught that “capitalism” is an economic system “preferred” by countries which, for historical reasons, rejected its supposed alternative, “socialism” or “communism”. We have been trained to use the word “capitalism” as a neutral, purely descriptive term. But is that really the case? Or does the word itself carry implicit assumptions? Perhaps we could begin to answer that question by investigating where the term came from, and when it entered everyday language.

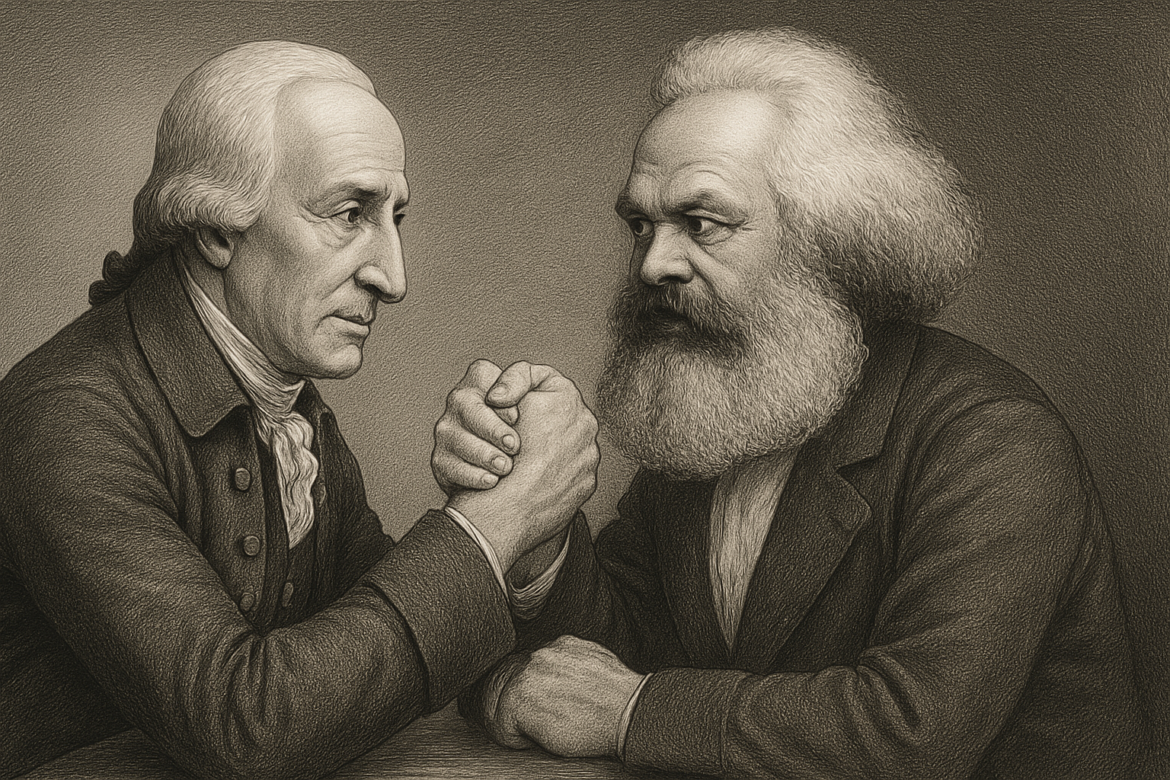

According to the most reliable studies, the first use of the word “capitalism” in its modern sense dates back to the mid-19th century, and it is generally attributed to Louis Blanc. Blanc, a French politician during the Industrial Revolution, is often regarded as one of the founding figures of French socialism. Unsurprisingly, in his 1851 work “L’Organisation du Travail”, he introduces the neologism “capitalism” as follows: “What I call ‘capitalism’- that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others”. After Blanc, the term was popularized by another French thinker, Proudhon – best known for coining the phrase “property is theft” in his first political pamphlet – and, of course, by Karl Marx.

Already, we begin to glimpse the ideological roots of the term. But, to truly grasp the issue, it is even more useful to explore how the term spread across Western languages. By using Google’s Ngram Viewer – which tracks the frequency of specific terms in published books between 1800 and 2022 – we can uncover some intriguing patterns.

Starting with the analysis of these data, it is probably clearer to distinguish the situation in French, German, Spanish, and Italian, on one side, and the situation in English, on the other, leaving this one for later. In fact, the word “capitalism” followed, in these first four languages, a fairly consistent trajectory. Its usage began to rise in the early 20th century, with the first noticeable peak occurring between 1930 and 1945 (notably, in German the initial peak came in 1933 – a curious coincidence, to say the least). But the real boom came later. Between 1975 and 1985, capitalism reached its all-time high across these languages (1975 in German; 1976 in Italian; 1978 in Spanish; 1982 in French), before experiencing a gradual, though not definitive, decline.

How does your mind react when reading those numbers? While you ponder that, let me share my reaction, and then you can compare it with your own. To me, the data makes perfect sense. Setting aside the specific historical differences, the period from 1930 to 1945 is that one in which the role of the State completed that metamorphosis which moved its first steps during World War I. The classical liberal doctrine that had previously guided government policy faded into memory. States increasingly sought to monopolize and regulate nearly every aspect of individual life. Even those regimes that ostensibly opposed socialism or communism – such as fascism and nazism – actually adopted politics which were everything but coherent with those resounding statements.

Without delving too deeply into country-specific histories, we can still outline a general trend: the rise of the social(ist) State, displacing the liberal one. The 1929 crisis – and a misinterpretation of the already questionable Keynesian economics – served as a convenient pretext to complete this transition.

And what about the sharp rise between 1975 and 1985? To me, that trend is even more revealing. This was the aftermath of the tumultuous late 1960s – a time when the democratic world witnessed an unprecedented surge of left-wing political influence. In the 1972 German Federal election, the Social Democratic Party achieved 45,8% of the votes, its highest score to date. In 1976, the Italian Communist Party garnered an historic 34,4%, challenging the long-standing dominance of the Christian-Democrats. In 1981, François Mitterand became the first socialist President of the French Fifth Republic. In 1982, Spain’s Socialist party won an astonishing 48,1%, in only the third free election following Franco’s dictatorship

The subsequent decline in usage of the term is equally easy to explain. The late 1980s saw the rise of neo-liberist thinking, its growing influences marked by political and economic victories. As well as, of course, the implosion of the U.S.S.R. And, therefore, the definitive collapse of the dream of many- sigh!- of spreading communism around the world.

All this considered, we can confidently say that capitalism is everything but a neutral word. If this evidence means anything, it is that the term is ideologically charged. Coherently with the ambition of certain political parties of dominating the public opinion, it started to be considered as an everyday expression when these parties had more power than ever. Even though the term’s popularity has declined somewhat, the ideological groundwork has long since been laid. Today, capitalism is still taught in schools and universities as if it were a neutral, analytical category.

Now, if you have made it this far, another question may be forming in your mind. We have covered the how and the when, but not the why: why did the term gain so much popularity, first in niche political circles, and then in mainstream usage?

You may agree or disagree, but to me the answer is as clear as a summer sky at noon: because the term serves a rhetorical purpose. It allows for a poisonous, yet seductive, interpretation of reality – one in which capitalism and socialism are seen as two equivalent systems, placed side-by-side on the same moral and historical scale. As if they had equal dignity, or could be reasonably compared.

But they cannot. And they never could.

Capitalism is the natural outcome of voluntary economic interactions among individuals seeking mutual beneficial outcomes. Socialism, by contrast, cannot exist without a centralized, coercive power imposing its will and restricting individual freedoms. It is a system promoted by a few in the name of equality, yet it invariably results in suffering and scarcity for the many, while enriching a powerful minority.

Capitalism is natural. Socialism is imposed. Capitalism means liberty. Socialism means restrictions. They do not, and never will, have the same dignity, despite everything this distorted world tries to make us believe.

Oh – and before I forget. I promised to return to the case of the English language. Can you guess when the word “capitalism” reached its all-time peak in English between 1800-2022? 2019.

I will let you draw your own conclusions.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the magazine as a whole. SpeakFreely is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.