Has your local hospital ever faced a shortage of essential resources like plasma or blood? Or maybe you’ve wanted to donate, but couldn’t find the time because of work, or because financial pressures simply don’t allow you the flexibility to take time off? For many Canadians, especially those living paycheck to paycheck, donating isn’t just about willingness, it’s about economic reality. These problems, and many more, stem from a single, overlooked policy failure: Canada’s ban on compensated blood and plasma donations in several provinces.

Canada’s stance is deeply rooted in the legacy of the tainted blood scandal of the 1980s and early 1990s and the subsequent Krever Commission, which emphasized voluntary, unpaid donations as a cornerstone of ethical blood collection. While these policies were well-intentioned, they have since hardened in provinces such as Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, despite evolving science, international best practices, and modern ethical standards.

This regulatory rigidity presents both a challenge and an opportunity. On one hand, entrenched stigma and institutional inertia still shape the debate. On the other, shifting global norms, provincial exceptions, and growing public support for pragmatic healthcare reform create fertile ground for progress. The Blood and Liberty campaign is poised to seize this moment by reframing the conversation, building cross-ideological coalitions, and advancing policies that honor both individual rights and public health priorities.

At the heart of this issue is an ethical contradiction. The ban on compensation is often justified by the desire to preserve the “purity” of altruistic donation. But this perspective disregards donor autonomy, and reinforces outdated assumptions about human motivation. Compensation does not eliminate altruism; many people are driven by both a sense of civic duty and financial necessity. By refusing to compensate donors, Canada’s current policy disproportionately excludes low-income individuals who may wish to contribute, but cannot afford the opportunity cost.

Public attitudes are also evolving. Younger Canadians increasingly support policies that emphasize bodily autonomy, fairness, and evidence-based approaches rather than paternalistic restrictions. This shift presents a unique opportunity to redefine the narrative, not in terms of risk and stigma, but as a matter of justice, empowerment, and practical ethics.

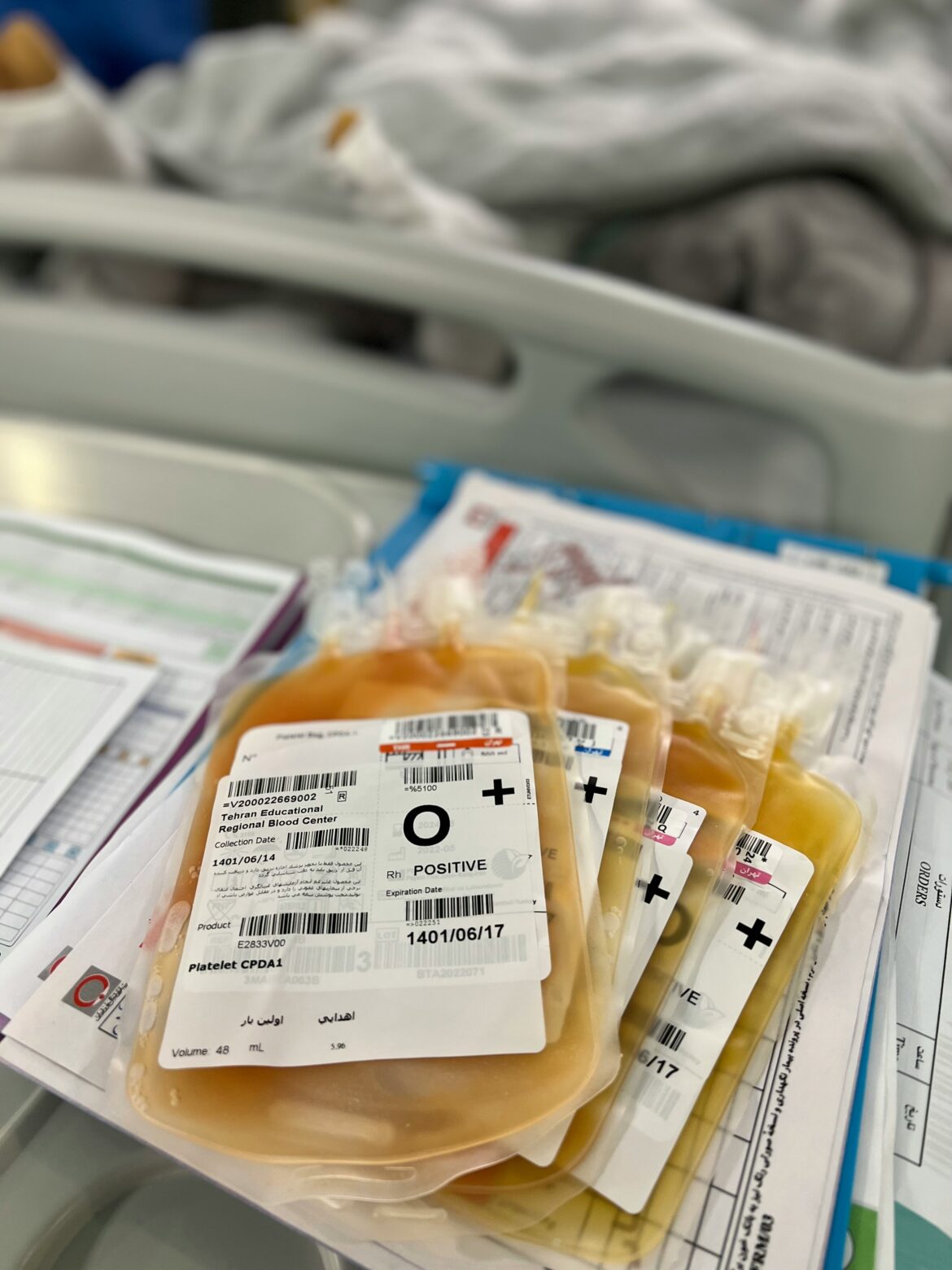

Meanwhile, the facts are hard to ignore: despite these bans, Canada imports approximately 80% of its plasma-derived therapies from countries that do compensate donors, especially the United States. This creates a paradox where we depend on paid donations abroad while refusing to allow them domestically. If the ethical concern is exploitation, why is it more acceptable when it happens in another country? All this does is benefit the American while denying Canadians both the freedom to participate and the chance to strengthen our own

Compensating donors is not coercive if done ethically. In fact, offering compensation can be a form of respect, a recognition of the time, effort, and personal contribution each donor makes. For many, this could be the difference between donating and not donating. The choice between earning income and helping others should not have to exist at all.

Critics argue that payment corrupts the moral value of donation. But altruism and compensation are not mutually exclusive. Acknowledging someone’s contribution does not diminish the ethical value of their act, it enhances it by making it more accessible to those who want to help but need to be supported in doing so.

A more practical look at the economics is no less bleak. On average, one liter of plasma costs around $200 before taxes, transport, or administrative costs are included. That adds up quickly. With the vast majority of our supply coming from abroad, we’re spending millions in public funds, not on patient care, innovation, or infrastructure, but on buying what we could easily produce at home.

More than just wasteful, this is risky. Canada only meets about 16% of its domestic plasma demand. That means if the U.S. changed its export policy, or global supply chains were disrupted, Canadian patients would face immediate shortages. No country should rely on foreign sources for something so essential, especially not when the solution is within reach.

Canada’s current plasma policy is ethically inconsistent and practically unsustainable. It’s time to move toward a regulated, compensated donation system, one that reflects modern values, international standards, and, most importantly, respect for both donors and patients.

We can no longer afford to let outdated ideology stand in the way of ethical and effective healthcare.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the magazine as a whole. SpeakFreely is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.