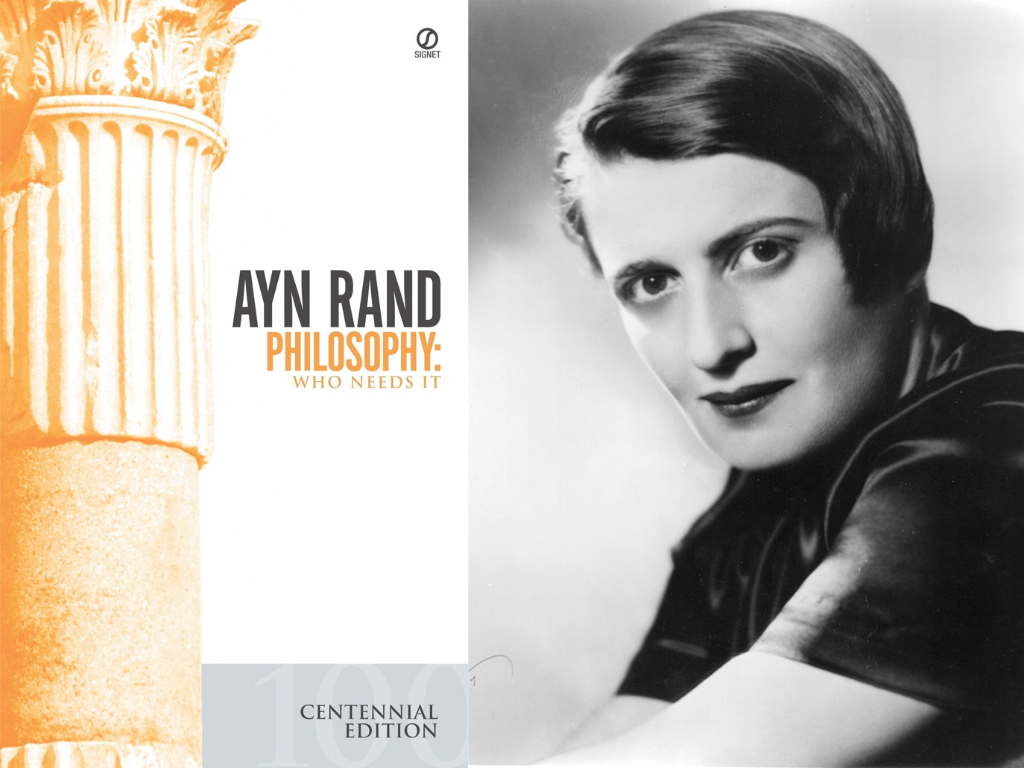

I was in an Uber, rereading Philosophy: Who Needs It—because nothing pairs better with morning traffic than unyielding metaphysics. Rand’s words, crisp as ever, cut through the noise: “There is no room for the arbitrary in any human activity.” Outside, a cyclist ran a red light. The driver cursed. I underlined the sentence. Then laughed.

Because if there’s no room for the arbitrary, why does the world feel designed to run on it?

Maybe that’s the point. Modern life thrives on a kind of engineered vagueness—an aesthetic of meaning without the burden of it. Fast content. Shallow headlines. Decisions made by algorithms. Everything is streamlined for efficiency, not understanding. It’s a world built not to be questioned. And the more I think about it, the more I realize: the machine doesn’t want philosophers. It wants obedience.

Philosophy, at its core, is the refueling of human consciousness—the air we breathe in the mind. Whether we realize it or not, every choice, every belief, every impulse we have has been influenced by some philosophy. If we ignore that, if we refuse to engage with it, we leave ourselves vulnerable—open to manipulation by the worst among ideas.

Think of it like this: the quality of a computer’s output depends entirely on the quality of its input. So, what are we feeding our brains? What kind of content shapes our thoughts and feelings? The endless scroll of distraction or the hard questions of truth, justice, and freedom?

Rand offers a seductive alternative: absolutes. She doesn’t ask you to trust her—she demands you think. A is A. Identity is non-negotiable. Logic is law. In a culture obsessed with vibes and relativity, this kind of philosophical clarity is electric.

But the real world is never that neat. Aristotle said humans are rational animals, but he never claimed we are consistent ones. Kierkegaard reminds us, “Life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.” Rand would’ve rolled her eyes at that. But maybe that’s why we need both—Rand’s steel and Kierkegaard’s smoke.

There’s a paradox in loving Rand: you learn to think independently, only to realize that the world doesn’t work on clean conclusions. And neither do we.

The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as intended—to distract, pacify, and reward conformity. Social media offers expression without introspection. Education teaches utility, not philosophy. We’re over-informed and under-reflective.

Even Rand, prophet of individualism, becomes a brand: slogans, aesthetics, memes. Who is John Galt? A question for T-shirts now. But if you dig deeper—past the quotes and caricatures—you find a genuine invitation to resist mental passivity.

In that way, she’s a gateway drug for brain usage. Philosophy can be difficult, even dangerous. It’s an act of self-protection, a defense of truth, justice, and freedom. If you don’t understand the theories, you’re vulnerable to the worst abuses. But when you engage, when you wrestle with ideas, you reclaim your mind.

The car stopped. I tipped the driver, an act that might have been guilt, kindness, or habit. I’m not sure. That’s the space Rand never helped me with: the space between logic and life. I walked into work, the city still humming with contradiction. The book stayed in my bag.

And for a moment, I was thinking—not scrolling, not reacting, not consuming.

Thinking. And in this world, that might be the most Randian act of all.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the magazine as a whole. SpeakFreely is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.