Politicians are often spurred into action during economic crises—they vote for massive stimulus spending which, they argue, will help the economy grow.

At first, the argument that massive infrastructure spending creates jobs might seem like a simple self-evident statement: when people build roads, they receive paychecks that they then spend, therefore stimulating the economy, right?

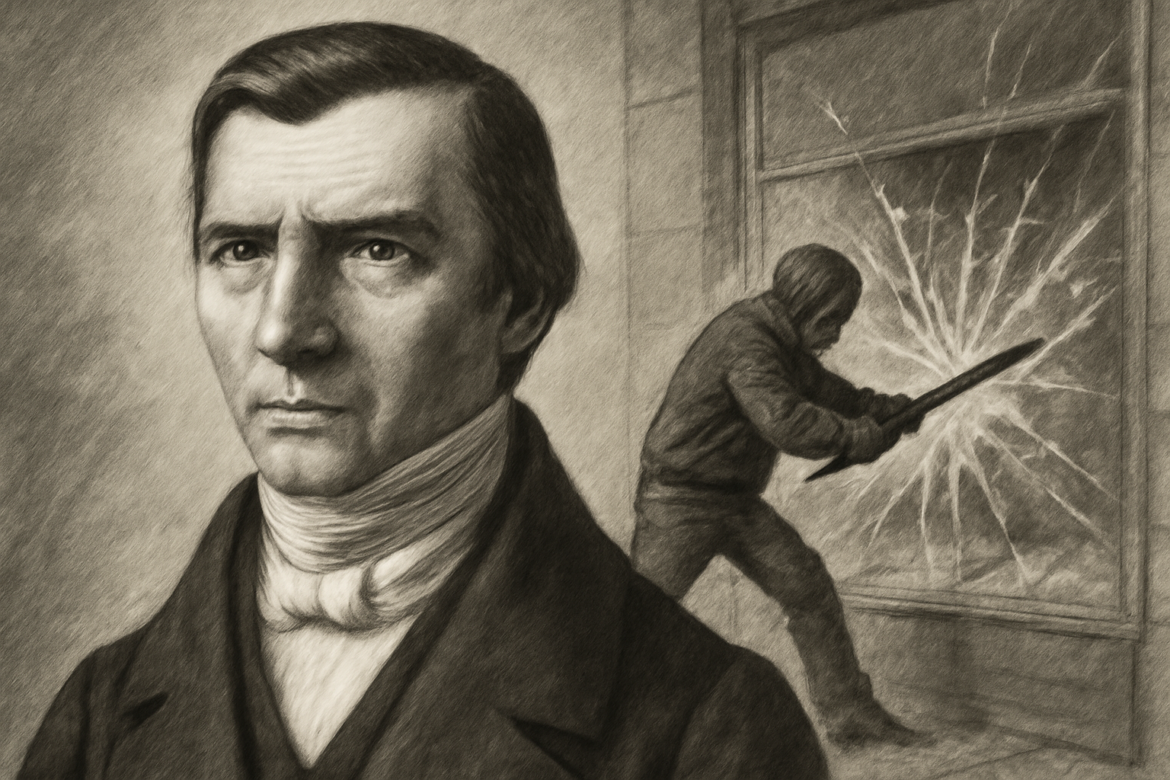

Imagine this: a vandal throws a brick through your window. You pay money to fix it; the repairman uses that money to buy food; the restaurant later hires a new waiter with that money. At first glance, it might seem like a great stimulus for economic growth. But is it really?

It’s important to remember that the neighbour’s actions do not account for YOUR plan with the money—alternative economic activities that you might otherwise have taken. You could have spent this money on a transaction that could have stimulated the economy in a more efficient way, like starting a business or investing in the stock market. The same argument applies to taxes and government spending. Every dollar of any budget or appropriation bill will always be paid for by the taxpayer either through direct taxation (Income Tax, Capital Gains Tax, etc.) or indirect taxes like inflation.

This is not a new argument. The ‘broken window fallacy’ was unveiled way back in 1850 by French economist Frederic Bastiat, in his essay “That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen”. However, in recent decades the work of the economist is largely forgotten and considered irrelevant by mainstream economists—and even well-respected right-leaning economists seem to have turned on Bastiat’s ideas through their advocacy for massive spending programmes at times of economic turmoil. They argue that while the free market is efficient in times of prosperity, the government must interfere during economic crises by providing fiscal stimulus to grow the economy. The argument is essentially the same: by providing jobs for the unemployed, the government can resurrect economic growth as those erstwhile-unemployed people can now spend their income, providing businesses with resources to ramp-up hiring and therefore bringing the unemployment rate down. The argument seems self-evident and tested, as the New Deal and Obama’s fiscal stimulus spending seem to have saved the US economy from 2 of the worst crises in their history. That notion is accepted by the general public as an axiom, repeated even by established conservative politicians and economists like Stephen Harper, Donald Trump and Ben Bernarke (through Quantitative Easing). However, as we will see below, the entire notion is built on inaccuracies and misconceptions.

The Untold Story of the New Deal

The New Deal didn’t save America as many people claim it did. We must first acknowledge that Herbert Hoover (Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s predecessor) was not a champion of laissez-faire capitalism. He signed the Smoot-Hawley tariffs, carried out mass deportations and oversaw one of the largest peacetime tax hikes in history to pay for massive public works programs like the construction of the Hoover Dam. Yet, by the time he left office, a quarter of the population was unemployed. If we look at the record of the Roosevelt administration specifically, we see that from 1933 (Roosevelt’s inauguration) to 1940 (the ramp-up of production in response to growing demand for military equipment as a result of World War 2) the unemployment rate never fell below 14%. For context, the average unemployment rate during the 1920s was 5%. The New Deal couldn’t bring unemployment below TRIPLE the normal rate. Every aspect of a Keynesian economic recovery indicated that the economy should have thrived: FDR committed to deficit spending until 1937, and by 1938 even the money supply recovered to its pre-crisis level, yet price and wage controls and high taxes that funded the programs kept the private sector weak. Perhaps later stimulus fared better, as economists learned from the failures of the New Deal.

Latest Stimuli

The most recent example of the failure of fiscal stimuli was the COVID-recession. Despite 3 rounds of helicopter money, personal consumption expenditure barely grew in the year 2020. After the economy largely recovered, the Biden administration needlessly injected almost 2 trillion dollars into the economy through the CARES Act. A recent MIT study says that such spending is responsible for half of the runaway inflation of the early 2020s. However, the biggest example of the inefficiency of centrally planned recovery was the Great Recession.

Failure of the Great Recession Stimulus

Over the course of 4 years (2009-2013) the government spent a total of close to 1 trillion dollars in bailouts, benefits extension and relief programs, yet by 2012 the unemployment rate still hovered around 8%. At the peak of the economic downturn, unemployment was 9.9%, not even double digits. Some may argue that spending helped prevent a sharper turmoil, but I would argue that if spending a trillion dollars is barely enough to stop the downturn, we need to find other solutions.

Laissez-Faire recovery

Contrast this with the economic record of the Harding-Coolidge administration. They inherited an unemployment rate of 11.7. They cut the top Marginal Income Tax rate from 73% to 24% and nearly halved government spending. By 1923, the unemployment rate was down to 2.4%. To measure economic activity, we can look at federal tax revenue. As mentioned previously, from 1921 to 1928 the top marginal income tax rate was cut from 73% to 24%, yet, tax revenue went up from 1.065 billion USD to 1.116 billion dollars. The share of tax revenue that high-income earners paid doubled from 29.9% to 65%, indicating high-levels of investment. You might argue that the recovery was natural and happened due to transition from a war economy to a peace-time economy. However, to prove the efficiency of a laissez-faire approach to economic recovery we can look at the US recovery from the recession of the 1980s, which was very similar to the Great Recession.

The Reagan Miracle

The unemployment rate reached 10.8% in 1982 – the highest since the great depression. Reagan cut government spending significantly in 1983. Quarter-on-quarter inflation-adjusted government spending contracted by an average of 1% in 1983, which was the peak of the recession marked by the highest unemployment in post war history (almost 11%), yet the recovery was strong and by 1986-1987 unemployment had almost halved and real worker compensation had spiked. Laissez-faire economic recovery seems very counterintuitive to many, so why does it work?

Why?

Governments are very inefficient by default. Most attempted recoveries end up stalled by massive bureaucracies and poor resource management. Politicians would rather invest in their districts than where it is most needed. The government also pays for its programs through taxation, taking money away from job creators. A pattern noticed across all attempts at centrally-planned recoveries is that the velocity of money slows down significantly, meaning that money is being hoarded by consumers, not spent or invested by small businessmen (this was especially true after the 2008 crisis recovery).

Seeing the Unseen

It is definitely tempting to examine only the ‘seen’ – it is much easier and more comfortable. But remember that every dollar spent by the government is a dollar not spent by a family business owner. The opportunity cost of government spending is a TV never bought, a business never opened, and innovations never funded. Next time you see a massive infrastructure bill, ask yourself what unseen consequences it will have. The path forward is not more taxes and more spending. We have tried that before, and it didn’t work. We need to cut taxes, slash regulations and remember that politicians don’t create growth; businesses create growth—let’s make these unseen opportunities real.