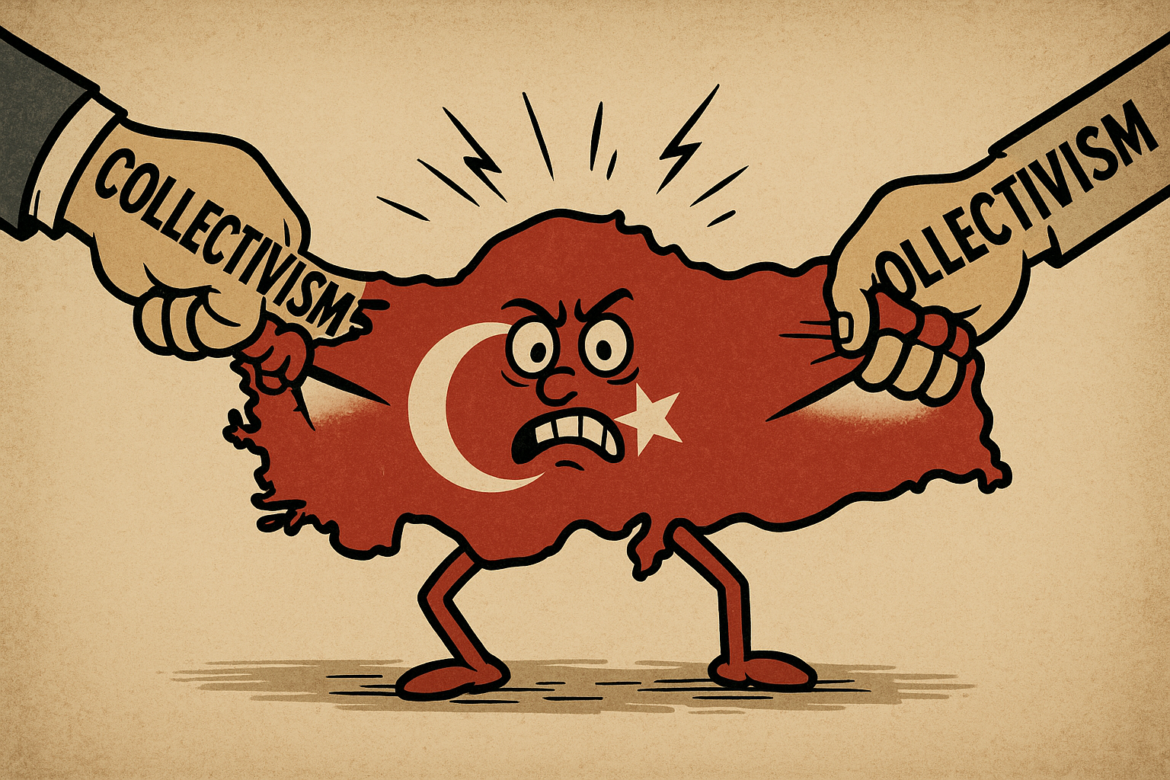

Growing up in Turkey, one often hears: “This country takes one step forward, two steps back.” This saying reflects a repeating cycle of state dominance and fragile freedom. At times, the country leans left, enforcing strong government control. At other times, self-proclaimed conservatives rise, but they too favor centralized authority, only in a different form. Individual liberty almost always comes second. Even in 2025, this pattern persists. The question remains: why has Turkey not broken free in a century?

The Early Republic: Modernization under Authoritarian Control

After the Ottoman Empire collapsed, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and İsmet İnönü led sweeping and radical modernization reforms. They sought to modernize the nation with secular laws, a standardized education system, the Latin alphabet, and cultural reforms. Politically, Turkey was under single-party rule through the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

While these changes modernized society, they came at a cost: dissent was suppressed, press freedom curtailed, and state programs limited local autonomy and religious practice. Economically, the Republic inherited Ottoman weaknesses, monopolies, centralized taxation, and fragile markets. Republican leaders feared unregulated enterprise would destabilize the nation. They instituted state monopolies, heavy regulation of private businesses, import substitution policies, and restrictions on foreign investment. These measures stabilized the economy but stifled entrepreneurship and entrenched the belief that the state must dominate economic life, a mentality that persists today.

The reverence for Atatürk and İnönü further cemented authoritarian norms. Both leaders are often idolized, overshadowing the fact that power was centralized, opposition silenced, and society tightly controlled. This normalization of state dominance shaped Turkey’s political culture for decades.

To be fair, the early Republic also introduced reforms that genuinely expanded individual liberty in the region. The adoption of the Civil Code, the abolition of religious courts, and the creation of a unified secular legal system marked a decisive shift toward the rule of law. Women’s rights advanced dramatically, granting Turkish women legal equality, civil autonomy, and political voice long before many European nations. The push for mass education, literacy, and civic identity helped break the power of religious hierarchies and local feudal authorities, giving ordinary citizens a degree of social mobility they had never experienced under the Ottoman order. These achievements did not eliminate the regime’s authoritarian tendencies, but they built a foundation on which any future liberalization in Turkey became possible.

The Democrat Party and Adnan Menderes

After the poor economic and living conditions during the single party and militarist & leftist İnönü era, the 1946 introduction of multi-party politics offered hope for freedom. The Democrat Party, led by Adnan Menderes, initiated economic liberalization, encouraged private enterprise, modernized agriculture, and promoted social freedoms including media diversity and relaxed religious restrictions.

Internationally, Menderes pursued closer ties with the West, joining NATO and encouraging foreign trade. Yet the Menderes era was far from flawless. Despite his early commitment to political openness, his government increasingly centralized power later on, restricted press freedoms, and used state resources to punish opponents, deviations from the liberalization he initially represented. Economic policy also drifted toward unsustainable populism, marked by heavy state spending and foreign borrowing that strained the economy by the late 1950s. These missteps do NOT justify the military coup that ended his life, since I support his liberal reforms and do not consider ANY military coup to be just. But that doesn’t change the fact that they reveal how a leader who began as a symbol of democratic reform gradually moved away from the classical-liberal principles he once championed.

Bülent Ecevit: Social Democracy and Its Costs

Bülent Ecevit, clearly the only innocent leftist politician with good intentions, rose to prominence in the 1970s as a social democratic leader from Republican People’s Party (CHP), advocating labor rights and increased state intervention. His government nationalized industries, expanded the welfare state, and promoted redistribution. While intended to protect citizens, these policies deepened economic dependency, increased bureaucracy, and fueled political polarization. High inflation, labor unrest, and escalating tensions between political factions culminated in the 1980 military coup, once again showing that state-centered policies, even with good intentions, could undermine both freedom and stability. Ecevit’s era also highlighted the limits of state planning in a rapidly changing global economy. Price controls and heavy regulation discouraged investment and pushed many industries into the informal economy. His government’s inability to curb violence between far-left and far-right groups eroded public trust, creating a climate where the military could once again justify intervention.

Turgut Özal and Partial Liberalization

Turgut Özal’s tenure (1983 – 1989 as Prime Minister, 1989 – 1993 as President) marked a notable turn toward economic liberalization. He privatized state-owned enterprises, opened trade, and encouraged foreign investment. Özal strengthened ties with the US and Europe and modernized infrastructure. Media liberalization and tourism promotion signaled cultural openness. Despite these reforms, political freedom remained limited, and the state continued to exert influence over civil society and judiciary. Özal’s era illustrates that economic liberalization can occur without full political liberalism, but that freedom remains fragile when state power persists.

The 1990s – 2025: Fragile Freedom and Increasing Control

EU-driven reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s expanded civil rights and strengthened civil society. Yet military influence, party closures, and political bans persisted. Subsequent governments further centralized authority, curtailing press freedoms and consolidating power.

After 2016, emergency decrees and restrictive regulations intensified state control, limiting civil liberties and weakening checks and balances. This period marks the harshest era for freedom in modern Turkey. The state adopted emergency rule as a governing model, issuing decrees that bypassed parliamentary oversight and reshaped institutions overnight. Tens of thousands were purged from public service, private assets were seized under unclear accusations, and the judiciary was reengineered to align with executive priorities.

The new presidential system of 2018 concentrated unprecedented power in a single office, weakening all checks, legislative, judicial, and local, while placing the bureaucracy under direct political control. Economically, the government pursued populist interventions, undermining market institutions through arbitrary regulations, pressure on the central bank, and politically motivated credit expansion. These choices reversed decades of progress toward economic liberalization, replacing rule-based governance with discretionary rule. Entrepreneurs faced unpredictable taxation, licensing pressures, and fines, narrowing the space for free enterprise.

By the 2020s, digital censorship, criminalization of speech, bans on peaceful assembly, and heightened surveillance became structural features of daily life. Civil liberties contracted to their lowest level since the military regimes of the 20th century. But this time not in the name of ideological discipline, rather under a hybrid framework of populism, hyper-presidentialism, and state capitalism. This clearly shows that those who call themselves “rightist” in Turkey are actually utterly connected to the leftist and collectivist policies in every aspect of ruling a country. In short, the Erdoğan period transformed Turkey from an imperfectly liberalizing democracy into a centralized, interventionist, and illiberal state. It demonstrates the core liberal lesson: when political power escapes institutional constraints, neither markets, nor civil society, nor individual freedoms can remain secure.

Breaking the Cycle

Turkey has not merely regressed, it keeps circling the same wheel. Across a century, the ideology of power shifted, but freedom has remained secondary. Left or so-called “right”, statist thinking dominates; the individual is connected to collective goals. Menderes, Özal’s and Erdoğan’s early liberal reforms show glimpses of possibility, yet every effort to increase freedom ran into state institutions that were too strong and unwilling to change. Bülent Ecevit’s social democracy demonstrates how even well-intentioned state intervention can exacerbate dependency and instability.

The 21st century offers a new chance, a society where the state serves NOTHING but the protection of life and property, leaving all other aspects of society to the free actions of individuals. History shows that this model works. Recent examples like post-World War II Western Europe, and earlier cases such as classical liberal experiments in 19th century Britain, the early United States and the Javier Milei government (La Libertad Avanza) which came into power in Argentina in 2023, demonstrate how freedom fosters prosperity and stability.

On the other hand, collectivist and socialist regimes have never produced comparable results. Instead, people have repeatedly risked death, as at the Berlin Wall, to escape them at the first opportunity. Only when the people of Turkey realize that collectivism and granting the state more authority is no solution, will Turkey finally break the cycle of collectivism and allow individual liberty to flourish just like its other European neighbors.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the magazine as a whole. SpeakFreely is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.