I remember when I first saw artificial intelligence (AI) generated art in 2021. Crouching beside my friend’s computer, the six humanoid creatures stared back at me with hollow eye sockets.

An image generated by DALL·E, a text-to-image model that specializes in art generation.

Brows furrowed. Eyes widened. Jaws dropped. I gasped. “What is this…creation?”

As an artist myself, I dismissed AI art generators, considering them horribly unskilled, sub-human creators with glaring inabilities to construct coherent art based on prompts.

But then, AI art rapidly improved.

How? By digesting published artworks. All 5.85 billion pieces of them. Enraged, artists attacked these seemingly “soulless” creations, describing them as everything from “a mashup of all the art we stole from artists” to “an insult to life itself.” According to a survey conducted by Colorado’s KOAA-TV, 76 percent of respondents claimed that AI images should not be considered art.

I disagree. AI art should be considered art, and in some cases, good art.

To understand my rationale, I will first explain what I consider “art” to be, and later what elements distinguish “good art” from simply “art.”

For me, art is not just an esoteric genre reserved for fancy black-tie galleries and high-nosed critics. Instead, I interpret art as any intentional creation meant to communicate meaning, evoke emotion, or explore aesthetic possibilities. Furthermore, when someone asks if a piece is “good,” I choose to not use jargon to discern it. Instead, I ask three simple questions:

How much skill is needed to replicate the artwork? Does it achieve the artist’s initial intention? And to what extent of effect does it have on the audience?

Skill matters, as it distinguishes an artist’s lucky accident from mastery; Intention matters, as it determines if the artwork hits or misses the initial goal the artist set out to create; Finally, effect matters, as an artwork that does not leave a lasting imprint on the viewer will simply be forgotten.

I arrived at this interpretation after synthesizing the two distinct definitions of art outlined by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ideas from traditionalists, who see art as something with aesthetic value, and thoughts by conventionalists, who understand art as a response to current events and history. I combined both ideas, as artworks are often created in the overlap between both definitions: crafted with skill, directed with purpose, and completed with profoundness.

Using these definitions, I realized that good AI art, like good human-made art, can still demonstrate real skill, clear intention, and a compelling effect. Looking at abstract art, for example, I would argue that Stadia II by Julie Mehretu is a better piece of art than No.5 by Jackson Pollock.

A side-by-side comparison of Mehretu’s Stadia II (top) and Pollock’s No.5 (bottom).

While both artists achieved their intentions and pioneered unique techniques, Mehretu’s detailed construction of an abstract stadium is far more difficult to recreate than Pollock’s sporadic drip method. Further, Stadia II addresses nationalism and revolution, which ties directly to history and current events, while No. 5 is far less grounded and instead speaks broadly to human consciousness.

This system also helps us distinguish the quality of AI art. Comparing Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason Allen and Grace:AI by Mary Flanagan, I would argue that the former is a more sophisticated artwork than the latter.

A side-by-side comparison of Allen’s Théâtre D’opéra Spatial (top) and Flanagan’s Grace:AI (bottom).

Both artists achieved their intentions, conveying meaningful messages about history and society. Specifically, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial explores the meeting point of Renaissance imagery and futurism, and Grace:AI reveals the stories of women artists often left unseen. However, creating Théâtre D’opéra Spatial required significantly more skill, including 900 prompt iterations and detailed editing in Adobe Photoshop, while Grace:AI relied more heavily on combining AI-generated portraits.

Under the same logic, there can also be significantly “worse” art. Some AI-generated images, like “Salmon in the River”—slices of frozen salmon placed literally inside a river—require no skill, have misguided intention, and produce no effect. Yet the same can be said of some human-created art; a haphazardly drawn line can be just as empty. The existence of poor examples does not invalidate the medium itself.

Salmon in the River, credited to @chatgptricks on Instagram Threads

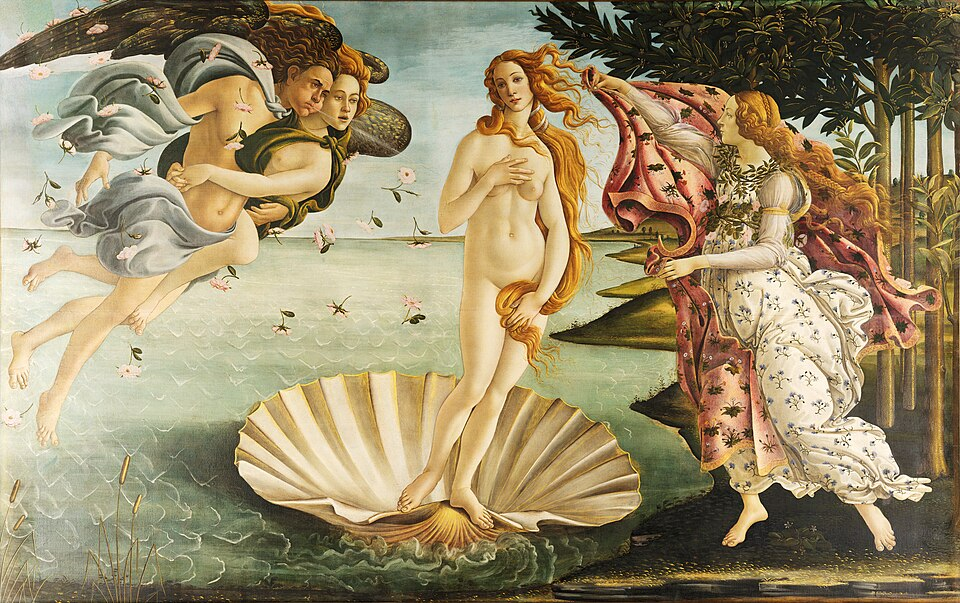

Concerns about intellectual plagiarism are understandable, but borrowing is not new. Botticelli adopted Greek visual language in The Birth of Venus, using the classical contrapposto pose.

Birth of Venus by Sandro Boticelli

Jacques-Louis David created the Oath of the Horatii from an ancient Roman legend.

Oath of Horatii by Jaques-Louis David

Artists have always borrowed from the past. AI simply accelerates a familiar creative process. Specifically, it identifies strong traits in existing art and shapes something new from them. By this standard, AI art that demonstrates genuine creative synthesis can be defended as transformative, even as ethical debates of its training data continue.

Today, AI expands the possibilities for artists. In companies, it automates roughly 26 percent of tasks once done manually. In the art world, creators use AI as a supplement, as seen in Hito Steyerl’s Power Plants, where artificially animated flowers bloom unpredictably throughout the exhibit. These examples show that AI strengthens artistic flourishing, instead of inhibiting it.

Power Plants by Hito Steyerl

Artificial intelligence is evolving, widening the creative horizon like never before. It is time for us, as innovators, creatives, and artists, to catch up to the speed of technology and celebrate a new renaissance of human expression.