In late 2025, the Georgian Dream party crossed a critical economic line. Faced with rising consumer prices and public frustration over the cost of living, authorities announced direct intervention in retail pricing, particularly in essential consumer goods. Officials justified the move as a defense of ordinary citizens against “unfair” markups and alleged abuse by large distributors. Yet price regulation is not a neutral action or a logical solution. It is a fundamental rejection of market coordination and a return to economic logic that Georgia once decisively abandoned.

For a country that built its post-Soviet recovery plan on liberalization, the reintroduction of price controls represents more than a policy misstep. It signals a philosophical shift away from individual choice and toward state coercion, with predictable and historically well-documented economic consequences.

Georgia’s Post-Soviet Break with Central Planning

Georgia’s modern economic identity was forged in opposition to central planning. Under Soviet rule, prices were administratively fixed, resulting in chronic shortages, the emergence of informal markets, and widespread systemic corruption. Price controls created an economic system in which demand permanently exceeded supply.

Following independence, Georgia initially struggled, but the decisive break came in the early 2000s. After the Rose Revolution, the government implemented radical market reforms: price liberalization, deregulation, tax simplification, and openness to FDI and trade. By the end of the 2000s, Georgia had become one of the world’s fastest-growing reformers, dramatically improving its business environment and reducing state interference in markets.

Price liberalization was central to this transformation. Allowing prices to reflect supply and demand eliminated queues, reduced corruption, and restored basic economic coordination. By contrast, the government’s decision to regulate consumer prices revives the very mechanisms that post-Soviet reforms were designed to dismantle.

The Political Logic Behind Price Controls

The political appeal of price controls is straightforward. In 2024-2025, Georgia experienced persistent inflationary pressure, with food prices rising faster than inflation. According to Geostat, food and non-alcoholic beverages were among the largest contributors to inflation, disproportionately affecting low-income families.

Government officials argued that price increases were not driven by global or economic factors alone, but by excessive markups in domestic retail chains. Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze publicly cited studies suggesting that supermarket markups in Georgia were significantly higher than in EU countries, framing price regulation as corrective to market “abuse”.

However, this narrative ignores structural realities. Georgia is a small, import-dependent economy with higher transportation costs, currency risk, and limited economies of scale, all factors that naturally raise consumer prices. Small open economies are especially vulnerable to external price shocks and have to focus on macroeconomic stability rather than administrative price control.

Blaming retailers may be politically practical, but it substitutes populist signaling for serious economic diagnosis.

How Price Controls Cause Problems

Most economists warn that price meddling always backfires. In a free market, prices balance supply and demand. A government cap distorts those signals. If, for example, bread costs $5 in an unrestricted market but is capped at $4, consumers will demand more bread than is available, while bakers earn less and bake less. The inevitable consequence is chronic shortages and rationing, a reality that Georgia already faced towards the end of the last century.

Georgia risks repeating this pattern. If retailers are forced to sell at capped prices, they will respond rationally: reducing product variety, cutting investment, or withdrawing from unprofitable segments. Over time, consumers face fewer choices, lower quality, and less availability, especially outside major cities.

When official prices fail to function, informal mechanisms emerge. Price controls in Venezuela, Argentina, and the former USSR consistently produced shortages and black markets, as documented by economists across ideological lines.

Georgia’s own Soviet experience provides a cautionary tale. Fixed prices never made goods affordable, they made them inaccessible. Access depended on connections rather than money, replacing market inequality with political privilege.

Georgia differs from the USSR and is an open nation, so the devastating effects that socialist countries faced in history are unlikely to repeat with the same magnitude. However, price regulation expands authoritarian power. Inspectors, regulators, and enforcement agencies gain authority to determine compliance, creating opportunities for selective enforcement and corruption.

Individual Sovereignty

The problem with price controls is not only economic but moral. Voluntary exchange respects individual autonomy. Buyers and sellers transact only when both expect to benefit. Government-imposed prices replace consent with compulsion. Once the state dictates prices, it must also regulate quantities, suppliers, and distribution, leading step by step toward a planned economy.

For consumers, price controls offer the illusion of protection while eroding real choice. For producers, they undermine the right to operate freely and sustainably. Individual sovereignty is diminished on both sides of the transaction.

The Real Path to Lower Prices

Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze has framed Georgia’s price problem as a story of retail greed. In public statements, he argued that consumer prices in Georgia far exceed those in EU markets, citing comparisons between the same international supermarket chains in Georgia and France.

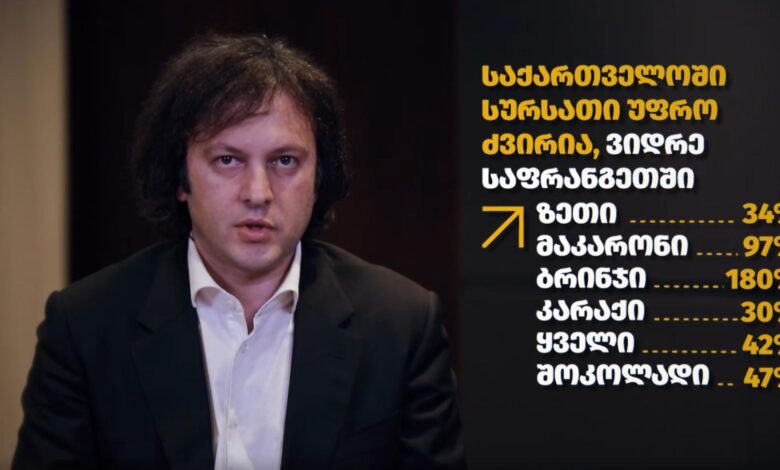

According to Kobakhidze, “the price of a specific brand of sunflower oil in Georgia is 34% higher, pasta 97% higher, rice 180% higher, butter 30% higher, cheese 42% higher, and chocolate 47% higher,” a disparity he attributes to what he describes as “excessive markups averaging 86% from Georgia’s border to store shelves.”

This framing has become the political foundation for price regulation. But while the numbers themselves may be broadly accurate in terms of total border-to-shelf increase, the interpretation is deeply misleading. The 86 percent figure does not represent a single predatory markup imposed by retailers. It reflects an entire cost structure, one in which the state itself is a major price driver.

A simple breakdown of the import-to-shelf price chain makes this clear. Take a product valued at 10 GEL at the Georgian border. The first increase comes from customs duties: a 12 percent import tax raises the price to 11.2 GEL. VAT is then applied not only to the product’s value but also to the customs duty itself. At 18 percent, VAT adds another 2.01 GEL, pushing the price to 13.21 GEL before the product has even entered the domestic market.

From there, real economic costs accumulate. Transportation adds 0.5 GEL on average. Warehousing, logistics, handling, and loss risk typically add another 5 percent, approximately 0.55 GEL in this case. At that point, the product already costs about 14.26 before any commercial profit is earned.

The importer then applies a margin, for example, a sensible profit margin of 10 percent adds roughly 1.42 GEL, meaning that the importer sells the product for around 15.68 GEL. Finally, the supermarket applies its own retail markup, using Kobakhidze’s argument of a maximum of a 14 percent margin, the final shelf price reaches approximately 17.87 GEL.

In other words, a product that entered Georgia valued at 10 GEL legitimately becomes a 17-18 GEL for consumers, not because of a single abusive markup, but because of a layered structure of taxation, logistics, risk, and commercial margins. The border-to-shelf increase is indeed around 86%, but that figure is the sum of many components. Critically, the largest guaranteed and non-negotiable portion of that increase comes from the state itself. Customs and VAT alone account for over 3.2 GEL of the original 10, roughly one-third of the border price.

This reality fundamentally changes the policy diagnosis. The problem is not primarily “greedy supermarkets.” It is a tax and cost structure that systematically inflates prices in a small, import-dependent economy.

If the government is genuinely concerned about making goods affordable, the real solution is to reduce import taxes, which would directly benefit consumers without distorting supply. Reducing VAT on essential goods would also immediately lower prices. Lowering regulatory burdens would increase competition among importers and retailers, driving prices down.

Symbolism vs Substance

Georgia’s price controls reflect a broader global drift toward economic populism, where governments promise immediate relief at the expense of long-term stability. Georgia’s success since independence has depended on rejecting the past economic model in favor of markets, openness, and individual choice.

Georgia does not have a markup problem. Treating these structural realities as retailer greed may serve political narratives, but it does not serve consumers. Sustainable affordability will not come from coercing prices downward, it will come from removing the state-imposed costs that push them upward in the first place.

Good reporting is cheaper than heavy-handed regulation. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.

This piece reflects the author’s views, not necessarily the entire magazine. We welcome a range of pro-liberty perspectives. Send us your pitch or draft.