Is it possible to reconcile the world of medicine with the principles of classical liberalism? Many consider the two realms entirely incompatible.

The clash is not just theoretical; it is personal, even emotional. Liberalism tells us that we are the authors of our own lives. Medicine, on the other hand, often assumes that someone else knows what’s best for us. What happens when a doctor says you must do something “for your own good”, but you don’t agree? That tension, between freedom and care, consent and control, can be a fracture hard to live with, especially as a libertarian in medicine.

This conflict is reflected even in the Students for Liberty membership structure. SFL has thousands of members worldwide, over 350 in Europe alone, and yet to this day, I have only met two medical students in SFL, other than myself.

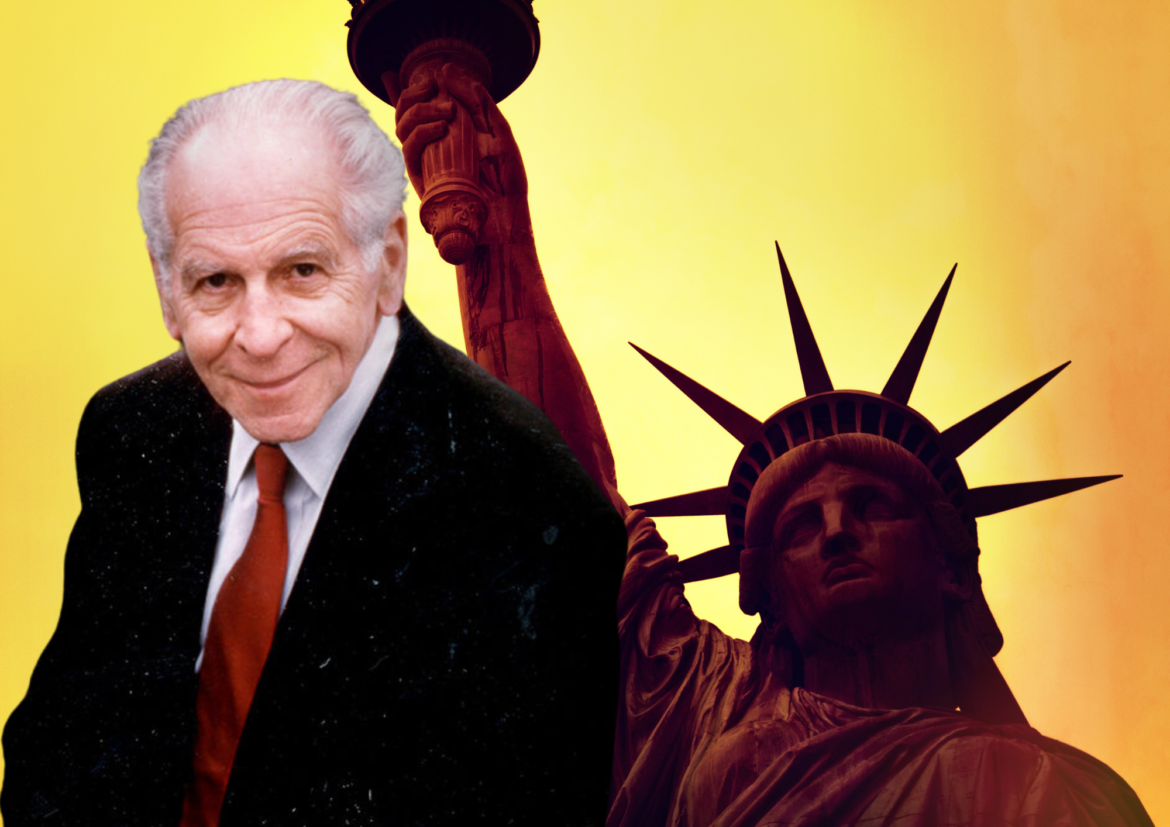

For a long time, I struggled with the conflict between the two disciplines, not knowing how to handle the contradiction. And then l discovered Thomas Szasz.

It was a thunderbolt. For the first time, I felt a little less alone. In Szasz, I recognised myself, and the same difficulties he faced over sixty years ago, caught between two seemingly irreconcilable worlds.

Born in Hungary in 1920 and trained in the United States, Szasz was a singular figure among both libertarians and psychiatrists. Among libertarians, he was met with suspicion, too close to medicine to be fully trusted. Despite being a consistent libertarian, he was seen as an outsider. He spoke in medical and scientific terms, which were hard to follow for those more accustomed to talking economics, law, or politics [1].

And yet, despite his fierce criticism of psychiatry, Szasz was by no means “anti-science.” Quite the opposite, he demanded the highest scientific rigour. He argued that real medicine is based on measurable biological facts, whereas psychiatry, more often than not, is not.

Psychiatry has changed enormously since Szasz’s time. Neuroscience has shed new light on many areas, but back then, his approach alienated him from the “alternative” or conspiratorial branches of libertarianism that rejected medicine entirely. Especially in the American context, where distrust of institutional medicine is widespread, Szasz’s insistence on scientific discipline and methodological clarity stood apart.

Moreover, he defended individual liberty with such intensity that even moderate liberals found him radical. Yet in psychiatric circles, Szasz was equally controversial. He was a psychiatrist who attacked psychiatry itself. He maintained that mental illness was not a true biological disease but rather a metaphor lacking scientific foundation. [2]

Szasz sparked widespread outrage and swift responses from all corners. Among his peers, he was often considered a traitor, someone who “bit the hand that fed him.” Unacceptable to many. And among libertarians, he was too academic, too clinical, too refined. He wasn’t a political firebrand but a thinker too nuanced for slogans.

In 1961, he published The Myth of Mental Illness, the book that detonated the uneasy coexistence between medicine and classical liberalism [1]. It didn’t just challenge the scientific foundations of psychiatry; it also exposed its moral and political assumptions.

Szasz did not deny suffering. He didn’t claim people were “faking it” or shifted the blame on them. But he warned of a dangerous confusion: calling something an “illness” when it isn’t.

Consider a man who becomes depressed after losing his job, or a woman suffering chronic anxiety in an oppressive household. Are we sure the proper response is a clinical diagnosis and pharmaceutical treatment? For Szasz, reducing complex life experiences to clinical protocols is not just simplistic; it is dangerous.

Institutional psychiatry, he argued, doesn’t just offer help, it defines what is “normal” and what is not. And in doing so, it robs individuals of their most fundamental right: the right to interpret their own experiences.

One of his most provocative lines puts it starkly:

“If you talk to God, you are praying; if God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”

It is a biting quote, but it forces us to question the thin, often political line between inner experience and mental illness [1]. What is sacred in one culture may be seen as symptomatic in another. But who gets to draw that line?

It is at this point that Szasz’s thinking becomes transformative for me, a libertarian.

Libertarianism starts from a core principle: the individual owns himself. Humans have the right to live as they choose, even in extreme or self-destructive ways. Personal responsibility is sacred [3].

Institutional psychiatry, on the other hand, is based on a paternalistic model: the doctor knows what’s best for the patient, even against their will. And in psychiatry, this becomes the power to decide that a person is no longer competent to choose. They can be institutionalized, sedated, and forcibly treated.

For a libertarian, this is unacceptable.

As Szasz put it:

“You cannot help someone against their will without at the same time violating their freedom.”

Involuntary treatment, forced hospitalisation, compulsory diagnosis, these, to Szasz, are forms of violence, justified by a scientific ideology. Think about it: if I steal a car, I’m guilty. If I insult my father, I’m sick. And in both cases, the State can intervene. The difference is that, in the second case, it does so “for my own good.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, Szasz’s ideas resonated widely. It was an era of rebellion, of mistrust in authority, of cultural revolution. He became a catalyst, though he himself rejected the label of “anti-psychiatrist.”

Over time, however, the tide shifted. Today, Szasz is nearly forgotten.

Of course, his ideas must be understood in context. Psychiatry then was very different from psychiatry today. Modern practice focuses more on the individual, their experience, and their autonomy. Neuropsychiatry has advanced enormously, helping us understand the brain and the mind in deeper, more integrated, and respectful ways. We are far from the era of asylums, closed in Italy thanks to Basaglia, who, in part, drew inspiration from Szasz’s work.

That doesn’t mean we have to agree with everything he said. Szasz was radical, provocative, and at times even paradoxical. But he had the merit of exposing the contradictions of his discipline and fueling a scientific and social revolution in psychiatry and psychology. Thomas Szasz was a heretic.

And that is precisely the role of heretics: To make us question what we take for granted.

1 comment

Excellent defense of Szasz as the heretic libertarian medicine needs, Mario!

Your personal struggle—caught between self-ownership and the doctor’s “for your own good”—nails the fracture Szasz exposed: psychiatry’s “illness” metaphor as a license for state violence, from forced hospitalization to denying autonomous choices. That quote (“You cannot help someone against their will without violating their freedom”) is gold, echoing how labeling dissent as disorder robs us of interpreting our own lives.

Bloody right on his outsider status too—too scientific for libertarians, too liberty-focused for shrinks. Yet his rigor demands we distinguish real biology from moral control, a revolution still unfinished despite neuroscience gains.

This resonates deeply with my recent essay on North America’s “The Forced Violence Paradox,” where Szasz’s final freedom (suicide as sovereign right, not pathology) meets policy: bans on humane death options coerce competent adults into traumatic methods, multiplying suffering under paternalism’s guise. Your piece revives Szasz perfectly for today’s fights—keep challenging the therapeutic state!

Thanks for making us question the sacred golden cows. Heretics like Szasz (and you) are liberty’s vanguard.