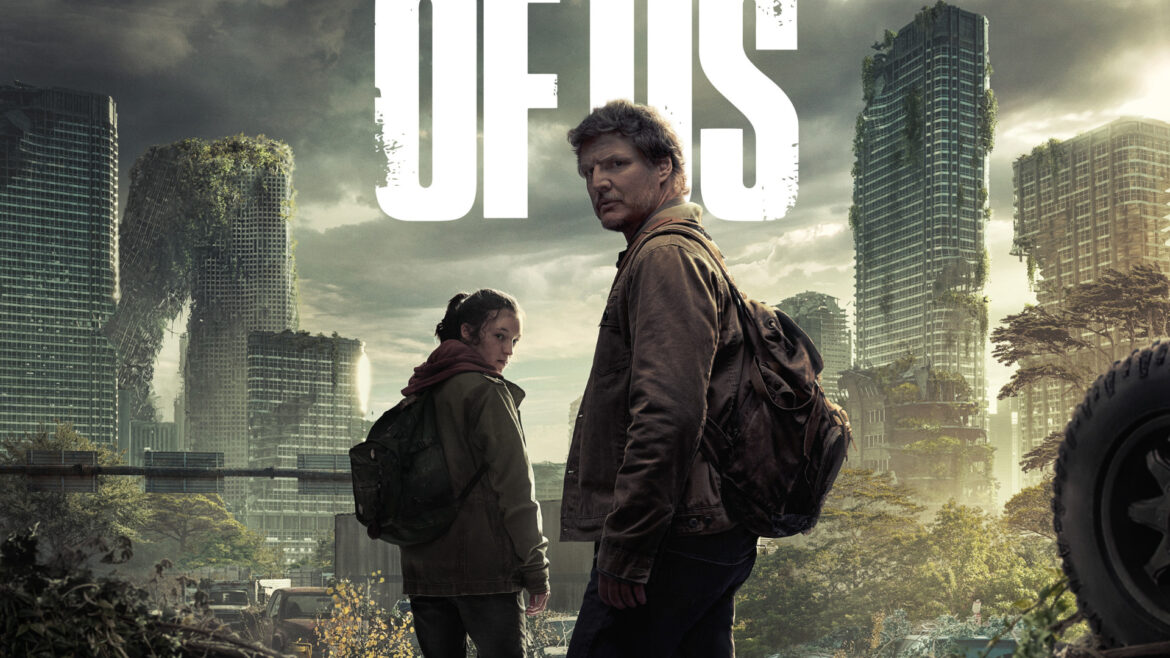

The Last of Us

A decade before HBO’s hit adaptation, The Last of Us was presenting gamers with a nuanced exploration of ethics, forgiveness, individual rights, and utilitarianism. The plot of TLOU follows Joel as he risks life and limb to bring Ellie, a 14-year-old girl immune to the Cordyceps fungus, to the Fireflies, a militia dedicated to finding a cure to the zombifying infection. Early in the game, Ellie and Joel are ambushed by cannibalistic scavengers known as “hunters.” Joel sees the ambush coming and narrowly defeats the hunters. When Ellie asks Joel how he knew they were being lured into a trap, Joel intimates that he used to be a hunter himself. For some indeterminate period of time, Joel survived the apocalypse by preying upon innocent people. By some moral standards, this fact should make Joel an irredeemable villain. And yet, by the time we’re playing as him, Joel is clearly not a bad guy. Beneath his gruff and ragged exterior, Joel is a hero, as evidenced by the innumerable perils he assumes to defend Ellie and save the world. In a state of extreme scarcity, Joel acted in ways properly regarded under normal conditions as morally impermissible.

Yet, when Joel is no longer in quite such a poor, nasty, and brutish circumstance, he behaves morally. In fact, Joel goes above and beyond the call of duty; his actions are supererogatory. In reality, as in The Last of Us, people don’t have perfectly homogeneous moral records. The vicious man who occasionally demonstrates humanity and beneficence shouldn’t be regarded as virtuous. Analogously, the virtuous man who morally errs ought not to be regarded as irredeemably vicious, provided he resumes his practice of virtue. To paraphrase Adam Smith in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, the remote effect of vice is often virtue. Joel is proof positive of this truism. Rather than tormenting himself with guilt, shame, and regret, Joel redeems his past viciousness by practising virtue in the present.

After many months and myriad near-death encounters, Ellie and Joel finally reach the headquarters of the Fireflies in Salt Lake City. Joel is informed by their leader, Marlene, that a lethal lobotomy is the only way to synthesise a cure to the Cordyceps fungus from Ellie’s natural immunity. After promising Ellie’s mother she’d protect her, Marlene reneges and decides to sacrifice Ellie for “the greater good.” Joel does not share Marlene’s utilitarian conclusion. Ellie is not conscious to consent to the surgery, so her will is unknown and unknowable. The ethical struggle is between Joel’s deontological respect for individual autonomy and Marlene’s rights-negating utilitarianism. If the player chooses a non-stealth route (as I did), Joel rampages through the Fireflies complex, laying waste to anyone who stands between him and the incapacitated Ellie. Ultimately, Joel rescues Ellie from the surgeons right before she undergoes the fatal operation. Before escaping the complex with his adoptive daughter, Joel is confronted by Marlene, who entreats him once again “do the right thing here.” Joel rejects Marlene’s cannibalistic philosophy, kills Ellie’s would-be executioner, and drives off into the sunset.

Joel’s rescue reveals the utilitarian pretence of subordinating individual rights to the will of the many for what it truly is: immoral hubris. The utility enjoyed by the many, even by all of humanity, cannot justify the coercive sacrifice of even one individual. Those who argue otherwise, like Marlene, do not believe in the inviolable dignity and rights of the individual. Such a posture begs the question, if humans are merely sacrificial lambs instead, what’s the point of sacrificing one valueless thing for the many?

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish is not just a beautifully animated children’s movie but an expert explanation of marginal utility and a thoughtful meditation on the katabasis; the ancient literary trope of the journey through hell. The movie follows Puss in Boots as he journeys with companions Perrito, a quixotic holy fool with a heart of gold, and Kitty Softpaws, a heartbroken cynic and Puss’s old flame. The goal? To reach a fallen star with the power to grant any wish.

Puss’s conflict is simultaneously intrinsic and extrinsic: the biggest obstacle to the wishing star is Death itself, represented anthropomorphically by a whistling wolf wielding akimbo sickles. Death has it out for Puss in Boots, who treats life with wanton disregard, disrespect, and ingratitude. Puss triumphs over Death when he stops trying to elude this inexorable foe. Puss courageously accepts the inevitability of his death by embracing the meaning, happiness, and beauty of his one life that he shares with his romantic and platonic companions. I understood the conclusion of the movie in economic terms. No, I mean it! Hear me out: instead of wishing for more lives, Puss realises that life’s meaning is supported—not thwarted—by its finitude. When you only have one life to live, you can’t afford not to live it well.

In economics jargon, Puss in Boots: The Last Wish illustrates the concept of diminishing marginal utility. Just like with all other goods, services, and things of value, the more one has of something, the less valuable is each additional unit. The first or, in Puss in Boot’s case, the last – life you have to live is the most valuable, most significant, and most enriching. The hard budget constraint of time alive encourages us to spend this invaluable resource well.

Not satisfied with teaching one profound moral and economic lesson, the writers of The Last Wish innovate on the katabasis of Greek and medieval legend. Dante’s Inferno, the first book of The Divine Comedy (1321AD), documents the author-protagonist’s journey through the nine circles of Christian Hell. Dante is accompanied by his literary and spiritual guide Virgil, author of the Grecian katabasis myth, The Aeneid, who ushers him through a hellscape existing for time immemorial. Puss in Boots, like Dante, is accompanied by cherished companions as he journeys through the Dark Forest to the Fallen Star. However, and this is the exciting part, the Dark Forest is not static but dynamic; its impediments are determined by whoever holds its magical map. When Puss in Boots holds the map, it shows the Valley of Incineration, Undertaker Ridge, and the Cave of Lost Souls, reflecting his intense fear of death. When Kitty Softpaws holds the map, it reveals the Swamp of Infinite Sorrows, the Mountains of Misery, and The Abyss of Eternal Loneliness, reflecting her fear of heartbreak following her abandonment by Puss in Boots. Unlike Dante’s Inferno or Virgil’s Aeneid, the heroes must struggle through a hell of their own making… literally.

Virgil, Dante, and Puss in Boots’ katabases remind us that suffering is often prerequisite to growth, enlightenment, and the achievement of one’s highest aspirations. Dante’s Inferno and The Last Wish emphasise that, as one proceeds through the bowels of hell, one must rely on the support guidance, and companionship of one’s closest friends. Even when the brimstone path is idiosyncratic, The Last Wish shows us that true friends are not fair-weather friends but companions through thick and thin.