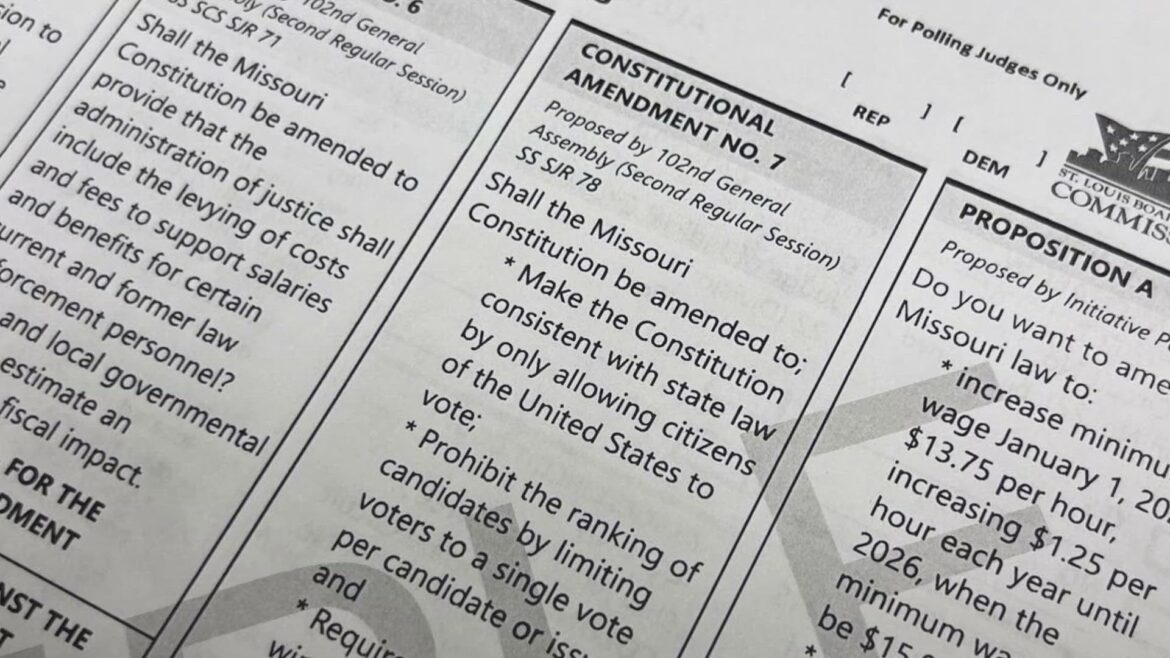

Missouri voters went to the polls in November 2024 expecting to decide on a straightforward clarification about election integrity. Instead, they were presented with Amendment 7, a constitutional amendment that combined unrelated issues into a single measure. On its face, the amendment declared that only United States citizens may vote, a rule already enforced by Missouri law. Buried within the same amendment, however, was a permanent ban on ranked-choice and approval voting, written directly into the state constitution. Voters were forced to accept both provisions together or reject both, even though they addressed distinct aspects of election law. The way this amendment was drafted raises serious questions about whether Missouri followed its own constitutional rules.

Amendment 7 passed with nearly 68 percent of the vote, a decisive margin. Supporters framed the measure as a commonsense affirmation of election integrity and citizenship requirements. That framing was effective, but it obscured the amendment’s more consequential provision. The citizenship clause was largely redundant, while the ban on alternative voting systems represented a substantial and permanent policy change. Critics argued that the amendment was structured to make rejection politically difficult by pairing a popular statement with a controversial prohibition, shielding the latter from meaningful scrutiny.

Ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference rather than selecting only one. Approval voting allows voters to support as many candidates as they find acceptable. Supporters of these systems argue that they encourage broader candidate appeal, reduce strategic voting, and limit the spoiler effect. Opponents argue they may confuse voters or complicate vote tabulation. Regardless of where one falls in that debate, Missouri communities had already begun to explore alternatives. St. Louis, for example, adopted approval voting for citywide primaries. Amendment 7 not only banned these systems statewide but did so at the constitutional level, foreclosing future experimentation. The amendment carved out a narrow exception for jurisdictions that had adopted alternative systems before the 2024 election, underscoring that the prohibition was not incidental but deliberate.

The core issue is not whether ranked-choice or approval voting is good public policy. The issue is how Amendment 7 was adopted. Article III, Section 50 of the Missouri Constitution requires that proposed amendments “embrace but one subject and matters properly connected therewith.” This rule exists to prevent logrolling, the practice of attaching controversial or unpopular provisions to measures likely to pass on their own. It is a structural safeguard designed to protect voters from being forced into all-or-nothing choices on unrelated issues.

The citizenship clause and the ranked-choice voting ban are separate issues. One concerns voter eligibility, the other concerns how votes are counted. They could easily have been presented as separate ballot questions. By bundling them, lawmakers shielded the ranked-choice prohibition from scrutiny and denied voters a real choice on that issue. Voters could not approve or reject the ranked-choice ban independently of the citizenship provision.

Some defenders of Amendment 7 point to a pre-election lawsuit as proof that the amendment was fair and legal. Two voters challenged only the ballot language, arguing it was misleading. The court ruled that the language was fair and allowed the measure on the ballot. That lawsuit did not address whether the amendment violated the single-subject rule, leaving the core constitutional question unresolved. Treating that narrow decision as proof the amendment is fully legal ignores the possibility that the bundling itself violated the Missouri Constitution.

The passage of time has not resolved the constitutional concerns surrounding Amendment 7. Missouri courts have long held that voter approval does not cure defects in the amendment process when mandatory procedural safeguards are ignored. The single-subject rule exists to prevent lawmakers from forcing voters into all-or-nothing choices on unrelated issues, and it remains enforceable even after an election has occurred. Because no court has yet addressed whether Amendment 7 violated this requirement, the central constitutional question remains open. Lawmakers cannot sidestep Article III’s safeguards without risking judicial intervention, and any future challenge could have strong legal grounds for success.

Missouri courts have previously intervened when amendments were adopted in violation of procedural requirements. Voter approval does not automatically cure constitutional defects. Past cases have clarified that structural safeguards exist to protect the integrity of the amendment process itself. When those safeguards are ignored, it undermines the legitimacy of the vote.

Missouri is not alone in this approach. Across the country, state legislatures have increasingly used ballot measures and statutory bans to preempt local election reforms, often by bundling popular language with unrelated restrictions. Florida banned ranked-choice voting statewide in 2022 despite no evidence of voter confusion or fraud. Tennessee and South Dakota passed similar prohibitions after municipalities explored alternative voting methods. In several cases, lawmakers justified these bans as voter-protection measures while simultaneously overriding local referenda or city council decisions. The pattern is consistent: state governments are using blunt constitutional or statutory tools to shut down local experimentation, even when voters themselves have expressed interest in reform.

Municipalities should be able to experiment with electoral reforms if their voters choose to do so. Innovation in democratic processes often emerges from local experiments. When state legislatures use constitutional amendments to foreclose experimentation, citizens lose the ability to influence election rules in their own communities. Amendment 7 created a permanent barrier, giving voters no meaningful opportunity to decide whether alternative voting systems could be used locally.

Voters deserved a clean choice. They did not get one. The amendment forced them to accept a package that included a redundant citizenship clause and a policy ban that could have been debated independently. Lawmakers prioritized political convenience over clarity, leaving citizens without a real opportunity to weigh the merits of the ranked-choice prohibition. The single-subject requirement exists precisely to prevent that outcome, but it was ignored in this case.

Missouri’s decision is significant because it demonstrates how easily constitutional safeguards can be bypassed when lawmakers are willing to package unrelated policies together. It is not a question of whether citizens support ranked-choice voting or not. It is a question of whether Missouri followed its own constitution when amending it. Until courts address the single-subject concern directly, voters remain denied a real choice, and the legitimacy of the amendment is in question.

Missouri’s Amendment 7 shows that self-government only works when voters are given clear choices and structural rules are respected. Citizens should not be forced into an all-or-nothing vote on unrelated issues. The state’s constitutional process exists to protect the integrity of elections, and ignoring it undermines trust in government. Missouri voters deserved clarity, and they did not get it. This is not just a debate about ranked-choice voting. It is about whether the rules of democracy are being followed. Lawmakers may have secured a quick political victory, but they did so at the expense of transparency, fairness, and the constitutional rights of the people.

Good reporting is cheaper than heavy-handed regulation. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.

This piece reflects the author’s views, not necessarily the entire magazine. We welcome a range of pro-liberty perspectives. Send us your pitch or draft.