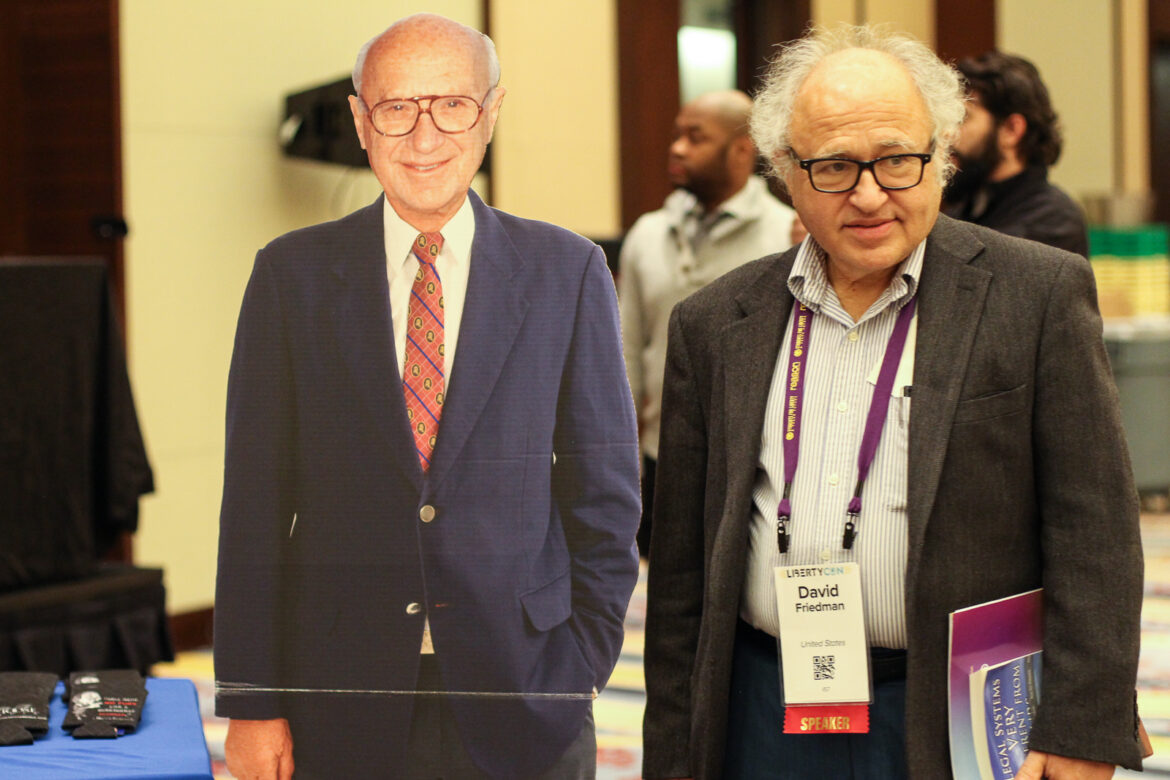

David D. Friedman is an academic economist with a doctorate in physics, retired from 23 years of teaching in a law school. His first book, The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism, was published in 1973 and includes a description of how a society with property rights and without government might function. There, as elsewhere, he offers a consequentialist defense of libertarianism.

His most recent non-fiction book is Legal Systems Very Different from Ours, covering systems from Periclean Athens through modern Amish and Romany. He is also the author of three novels, one commercially published and two self-published, and, with his wife, a self-published medieval and renaissance cookbook and a larger self-published book related to their hobby of historical recreation. Most of his work can be found on his web page: www.daviddfriedman.com, his current writing at https://daviddfriedman.substack.com/.

SpeakFreely (SF): I should like to begin by asking you- we live in an age of increasing unfreedom. The rather silly tariff thing of Donald Trump, the attacks on civil liberties in various parts of the world, war in

Ukraine, South Sudan, and Gaza. Given this, what is the individual liberal to do? Those that lack the voice and the reach and in some senses the infamy that you might have; those without the resources of, say, the organisers of this conference- the median public liberal, the median public believer in freedom- would appear to have no choice but to grin and bear it. So what are we to do?

David Friedman (DF): Well, you can try to make arguments. You can try to elect people who are less bad- and, I must say, in the last presidential election in the US, I did not vote for either of the major party candidates. I thought it was a choice between two different kinds of bad outcomes. But sometimes you have some choice, but mostly you can just live your own life and, you know, try to interact with people peacefully and try to make arguments and see if you can explain to people why what’s happening is wrong, and so forth. So, I mean, we’ve never been at a time when any single individual could control the world. It’s not- that’s not possible, obviously.

SF: Indeed. Also on the topic of voting, and both, parties- both candidates- seeming, you know, two versions of the same evil, if you will: to what degree, if any, should libertarians be agnostic to the established parties and political factions? A common argument advanced is the whole tactical voting thing, where, both parties might be bad, but one is necessarily less bad, and to vote for a third party is to waste your vote.

DF: From the standpoint of the individual, voting as a way of changing the world doesn’t make very much sense, because one vote has a very low chance of changing things. So I really think of voting mainly as an expressive activity, as something I do because it’s the equivalent of cheering for a football team, as it were, and neither of the football teams at the moment in the US is one that I want to cheer for.

But there is the argument that although it is not in my interest to vote for one party or the other to try to change things, it might be in my interest not to say so, in the hopes that other- than enough other people will vote in some way that will change things. I would say that the main view from the standpoint of a classical liberal or libertarian, the main use of political campaigns is a way of spreading ideas. That when you have a political campaign, people are thinking and talking about political issues, and you can then try to get in into that conversation. And one way is running a third party campaign. Other ways- sometimes supporting a candidate, maybe a candidate who won’t get nominated, but somebody who will get enough attention. Because the real objective, in a sense, is not to get the good party elected, because there usually isn’t one. It’s to get both parties to follow policies a little closer to what we want. And you can do that by changing people’s ideas.

SF: That does have some unique implications for the relation between liberty and democracy. To that end, I’d like to ask- how much of a comparison or overlap might there be between democracy and the market? Can we think of the vote as something approximating a price signal?

DF: No, I don’t think so. Democracy is not equivalent to a market. Democracy may perhaps be the least bad way of running a government, but it’s still a very poor way of running a government, because we don’t have any good ways of doing it. For one thing, on the market, if I spend my money on one thing, it’s not available to spend on something else, whereas I can vote to have one law in my favor and then another law in my favor and another law in my favor.

So there’s a sense in which the market is much more egalitarian than the political market, that in the market, if I have twice as much money as you have, I get to buy twice as much stuff, but don’t get to buy everything. On the other hand, if I’ve got twice as many votes as you have, I can win all of the contests.

SF: Do you think it’d be possible to sort of make democracy more like the market? In particular, I have in mind a system invented by a fellow you may be familiar with named Glen Weyl, something called quadratic voting. He says, you give people voting credits. And for the sake of fairness, you give everyone the same amount of voting credits. It costs one credit to buy one vote. It costs two to buy two, or perhaps four to buy two, and nine to buy three. The idea is the more votes you want, the more expensive it is (to buy them), if you will.

DF: And what are you buying them with?

SF: Well, you buy them to pick positions.

DF: No, but- what is the asset? What’s the “money” that you’re buying with?

SF: Well, it’s a grant, if you will, a kind of-

DF: So you’re saying each person’s got a certain number of votes-

SF: Of credits

DF: Certain number of credits

SF: Yes

DF: During the year?

SF: Per election, if you will

DF: Per election. And there are separate things that are being voted on?

SF: And you can choose how many credits you can accord to each- to each election, if you will. So I mean, if you want to- if you are so concerned about, say, an election on zoning laws- you use enough credits to purchase five votes. And that might mean you don’t put any votes at all on something else, like something you don’t care about. So I find that a fairly interesting way to make- the idea is market principles; you can “buy” votes and you can “price” the degree of preference you might have for a position. It might indicate some degree of ability to “marketise democracy”. And I wonder if you agree.

DF: My instinct is no, but I’d really want to think about it more carefully, to have an opinion.

SF: Of course. To segway into something completely different, you’ve spoken of limited examples of anarcho-capitalism in the past, and one of them is medieval Iceland.

DF: Iceland was what I usually describe as a semi-stateless society, because there was a single law code, although there was no executive arm of government, so that the enforcement was private, but there was a single court system and a single law code. The Somali system is a little bit closer. I think there have been quite a lot of stateless societies of one sort or another in the past; the Somali (model) actually comes a little closer to my kind of model.

This is the traditional Somali system, the Somali system that existed before the creation of the country of Somalia, existed in the northern half of what’s now Somalia, roughly speaking, and that was a system where the equivalent of my rights enforcement agencies was coalitions. And any individual was a member of a set of nested coalitions. It was quite a weird system. So your lowest level coalition mostly makes up the male line descendants of, I think your grandfather, or maybe your great grandfather. But it doesn’t have to be done by kinship. That is to say, you can form a coalition, which is just people who want to work together, and then if somebody wrongs you, and you end up with a feud, the other members of the coalition support you in the feud. If you wrong somebody and are judged and then decide to settle, as it were, they help you pay the damage payment. If the other side settles with you, they get a share of the damage payment. And part of what’s neat is that it really was an explicit contract; that we’ve got an example.

There was a British- Welsh, I think- anthropologist, who studied the system and wrote it up in some detail. And one of the things he gives you is an actual written contract, which I think was deposited with the British at the point at which the British were theoretically running that part of of Somalia, but not very much, stating what the agreement was within this coalition. But then part of what’s weird about it is that each coalition is then a part of a larger coalition. So if it turns out that your opponents are too strong for you, it escalates up to the next one. So a very, very weird and intricate system. It’s not identical to my anarcho-capitalism, but it has some of the features.

One of the things I liked about it, in terms of bargaining for legal rules, was there was a point at which there was an unusually high level of violence, and so the parties agreed to raise the damage payment for killing somebody. They raised the price of killings as a way to get less killing.

SF: That’s one way to price a life [laughs].

DF: Well, I just thought that was very neat- a sort of market approach to law, that they’ve got. In a sense, in any society, you’ve got trade-offs. You have certain things you want to prevent. You’re not willing to say, if you steal a nickel, we’ll burn you at the stake; you have to have some trade-off between punishment, and this was a case in which, in effect, a market bargain was determined on what the punishment was for a particular offence, in response to a level they didn’t like. So that was sort of neat.

SF: I suppose my counter question is bipartite. The first is- these were examples that existed some time ago and they did not produce anything approximating modern levels of prosperity, if you will.

DF: Well, very few things over the last couple of centuries have produced that.

SF: Well, it’s more like, how much can we learn from examples of stateless systems that existed

several hundred years ago?

DF: One of the things that you can learn is that it’s not impossible. You can see what the potential problems are; my reading of the breakdown of the Icelandic system- the system lasted about a third of a millennium, about 330 years or so- but the last 50 years involved, by their standards, an unusually high level of violence. And I think what was happening was it was becoming less competitive.

That is to say, you had a set of goðar- which is usually mistranslated as chieftains- who, again, were sort of like rights enforcement agencies, in the sense that any individual Icelander chose to be the kinsman of one of the goðar. But he could choose among them, and that determined where he’d fit into the legal system.

And one of the things that happens in the late period is that you have a single coalition that controls a whole bunch of the goðar so instead of 40 players, there are, like, three players, four players. And I think that’s a situation where it becomes less stable. So that would be one example where one of the issues that I discussed in The Machinery of Freedom, at least in the third edition, is the risk of cartelization; the fact that if you have a small number of rights enforcement agencies, they may get together and reinvent government in effect, on the grounds that a ceiling is more profitable than selling in a competitive market, and that’s partly inspired by what actually happened in Iceland. So that’s relevant.

But there’s a good deal of stateless law even in the modern world. (Robert) Ellickson has got a book that’s about the system of private norms in Shasta County, California, which is maybe a couple of hours from where I live, and certain issues are settled by non-state mechanisms. And as he describes it, one of the reasons that the state doesn’t get involved, is that one of the strong norms is that neighbors don’t sue each other, and therefore, if you try to bring in the official legal system, you have already violated the rules of the unofficial legal system. And since the unofficial legal system has its own enforcement mechanisms, it usually doesn’t pay to do that. So that would be an example.

The Romani have a sort of stateless system, along with various other things going on. The Romanichal- the British Romani- I like to describe as a primitive version of the saga-era Icelandic system 1000 years earlier, in that it’s the sort of the same underlying logic, but with a lot less structure. So you have examples, I think of elements (of statelesness).

And of course, if you think about it, a lot of what’s going on in ordinary, modern society is really stateless law enforcement. If you think about it, why do firms mostly not cheat their customers? There are lots of contexts online where I am, in effect, given a long contract that I’m asked to sign, and I don’t read it! And I expect almost nobody reads it, and the contract is theoretically what protects me. What really protects me is that this is somebody who wants my business, that if they cheat me in one transaction, I’m not going to go back to them. And your therefore have, in effect, a reputational market.

You have a fairly explicit reputational market with eBay. I don’t know if you’ve used eBay, but eBay is set up so that when you make a transaction, you get to report on whether you were satisfied with the behavior of the other party. And when you want to make a transaction with somebody, you can observe what his rating was, how many people thought that he behaved badly in the past. So that is a private, stateless law enforcement system that we’ve got running. Sort of quietly right around us.

SF: On a somewhat tangential note, it appears to me that there are some things that are good for the human race that require…scale. Things like scientific research, or nuclear power plants-they require significant scale; massive capacity on the part of some central authority-

DF: Why does it have to be a central authority?

SF: Well, that was going to be my question. Would you say there have been leaps in the human standard of living…

DF: But it’s not at all clear that they came from [centralised authority]- there’s a British researcher, and I’m now forgetting his name, but his book, I think, is called the Laws of Scientific Research, or something close to that. And he argues that if you actually look at the history, there are various points in one when one, some particular scientific area suddenly gets funded a lot, and that does not correlate with progress.

SF: The exact example I had in mind was perhaps a very crude one, which is that for hundreds of years, Germany was a collection of city-states, and that produced a degree of competition and literary output, I suppose. But it was only after Imperial Germany- the unification- that you got the leaps in the natural sciences, that 1/3 of Nobel Prizes go to German-trained scientists, perhaps because of the Humboldtian research university model of government-university partnerships. From that I wondered if that kind of scale and that kind of…”bigness”, if you will, was necessary for the advancement of innovation. You seem to think that confederations of very small groups of scientists could in fact, produce that much or even more innovation? If so, I would like to ask why.

DF: One of the problems that we observe at present with large-scale government subsidies to research is that when you have a single funder, you tend to get orthodoxies. You tend to get a situation where, once it’s sort of established what the official view that the senior people have is, you don’t get funded if you don’t support that view. And the particular example that I’ve been involved in in the last decade or so has to do with climate research. And I think I can show that the branch of it that deals with consequences- I don’t really have an opinion about the research on what climate change is going to be- what I’ve looked at fairly carefully is, what are the consequences for human beings of the projected changes? And I think it is clear that that is a very badly biased field, that you get journal articles published in respectable places that are clearly dishonest.

My standard example of this is an article, I think, in Nature, which is trying to estimate the cost of CO2. They are calculating it over 300 years, and the implicit assumption is no progress in medicine. Roughly half their cost comes from increased mortality due to warming. To begin with, any estimate of that is not very reliable, because it’s a very hard problem, given that warming both reduces cold mortality and increases heat mortality. But in particular, one of the things that surely mortality from temperature depends on is the state of medicine, and they are taking data. The book referred to is likely The Economic Laws of Scientific Research, by Terence Kealey from the recent past and applying it for 300 years- well, three centuries, a little less than that, 275 years, roughly. And that particular article spends a paragraph or two at the end on reasons why their estimate might be too low; they say nothing at all about the reasons why their estimate/ why you can be reasonably sure that half their estimate- is at least two or three times

too high.

Not only are they neglecting medical progress and not allowing for it. They’re not allowing for the effective rising income- richer people have air conditioning and better heating and don’t have to go out in bad weather and so forth. So that they have a model in which at the end of the period, per capita GNP is up about 11 times what it now is, but they assume that that has no effect on the vulnerability to temperature. So this is the case; I think, quite clearly, where they knew what answer would get them published and get them popularity, and I think this is not uncommon. That there have been a fair number of cases where a scientific claim was very widely supported with very poor reasons.

The one of these that I first got into, like 50, more than 50 years ago, was the issue of population growth. And it was the same issue, because what I was questioning was not the projections of population [growth], but the claims about the effect of population growth, and just as with with climate change, what was going on was that a change would have both positive and negative effects. Because the Orthodox position was that the net effect was negative, people looked at the negative effects and made generous estimates of them and mostly ignored the positive effects and then said, look, it’s terrible. And that’s a case in which we know they were wrong, because the orthodoxy of about the late 1960s maybe before that

SF: The famous Paul Ehrlich bet.

DF: Well, yes, that was Ehrlich’s projection that there would be mass famine in the 70s. It’s a little unfair, because although that was within the range of what was considered sort of respectable, it was at one end of the range. But the orthodox position, what everybody respectable agreed about, was that population change would make poor countries much poorer? Well, poor countries continue to increase their population, but the amount of extreme poverty dropped drastically. If you look at the graphs, the per capita consumption, calories per capita went up. So that was the case where you had sort of a respectable orthodoxy which turned out to be completely wrong, and I think a minor case of that which you’re not old enough to remember, but I am, is that on the question of saturated fats for heart disease. The view was

pushed pretty seriously, that one you should use margarine instead of butter, because butter had saturated fat. It turns out that the margarine they were using at the time, which was hydrogenated vegetable oil, consists of trans fats, which would turn out to be much worse for you than saturated fats.

So that was a case where there was an orthodoxy- and I don’t know how many people it killed, but it killed quite a lot of people. So in general, it seems to me that having a situation which there’s one source of funds which is mainly responsible for some area of scientific research tends to corrupt the project, and especially corrupts it if the conclusions have any political implications, because then each side wants to get control of it and use it to establish what they want.

SF: Gordon Tullock in the 1970s published, I think, a collection of essays titled Explorations in the Theory of Anarchy; it’s been republished recently under another title, I think, Anarchy, State, and Public Choice. And in his essay, which is entitled Anarchy, he points to the end of the Roman Empire, where we had effective private provision of security and some basic public services, and he suggests the providers of those services became the feudal lords of the medieval era.

DF: And income went up, at least the population. If you look at the population figures, it’s striking the difference between the sort of popular image and what the population data show. I take population growth in poor societies, which means everybody until the last couple of 100 years, as a rough proxy for income, and if you look at it, the population is falling in the late Roman period. It reaches its bottom, if I remember correctly, something like 5 or 600 AD, and it then starts back up.

And I think- I’m doing this by memory, so I’ve probably got my details right- but by something like

800 it reaches the Roman maximum and keeps going up. Goes up slowly by modern standards, that is, you’re talking about a fraction of a percent a year, not the kind of growth rates that we get in modern societies, because they were very poor societies. But so far as I can tell, the High Middle Ages were probably richer than the Roman Empire.

SF: You reject, then, the narrative of the medieval era being 1000 years of stagnation.

DF: Yeah, that’s nonsense. I don’t think anybody thinks that. Medieval historians don’t call it the Dark Ages- and the original reason, I think, for calling it the Dark Ages was not that things were terrible. We just didn’t know much about it. We don’t have the kind of good sources that we had before and after.

Now, the interesting comparison would be the Byzantine Empire versus the feudal West. Because certainly the Byzantine Empire could look very impressive because they were funneling the resources into the centre, but that means they’re funneling them out of other places. I think we tend to overestimate monarchy- absolute monarchy, the post-medieval system- because it’s pulling resources into the center, and that means you can fund artists, and you can build big monuments and so forth. But somebody is paying for that.

SF: I think Anthony Kaldellis is a very feted historian of the Byzantine Empire who seems to argue that late Rome and Byzantium generally were paragons of big government, as it were; provided service that interfered deeply into the lives of everyday citizens. He contrasts that in a very recent book of his called The New Roman Empire, with the medieval period in the West. I personally have “Byzantophile” biases; I think the comparison he makes is positive, but I’m not certain. Do you think it is possible to contrast that kind of centralization and provision [with the decentralised medieval West] favorably?

DF: I have guesses, but I don’t really know enough about it. In particular, I don’t know how good our Byzantine population figures are. Byzantines really did some impressive things, but I don’t know whether, on the whole, the areas they ruled were better off or worse off being ruled by them.

SF: I’ll make a tangent again and say there are certain populations that you would think make natural libertarians. So people, you might crudely call “oppressed people”- more generally, people of traditionally hated phenotype or ancestry, women, people of renegade political beliefs- are people you would think are natural libertarians, very wedded to civil liberties and property rights, because their chief oppressors have usually been the state. And yet, today, most such people are not libertarians; they are usually some kind of state-progressives. Why is that? And how might we change it?

DF: I don’t know. In general, there are very weak incentives to hold correct political views, given the general sort of rational ignorance problem. If you are deciding whether to be a classical liberal or a socialist or something else, the question of whether one system or another works or even works for people like you is not a very high priority. It’s more important to know what are, what is the political position that will make the people you care about like you. I don’t have a good theory of how that, how that happens, but all I’m saying is that the connection, the ways that political mechanisms produce correct results are not very good.

SF: I think I’ll ask two final questions before we end. The first is mostly me providing a bit of pushback to a comment you made yesterday in your talk, that being the positivity, the desirability of a world culture. I remember reading a paragraph- I forget where exactly- which said you could hold a party in medieval Germany, and there’d be people from Lubeck and Munich and Westphalia, and you’d see many different dialects and many different costumes, many different original cuisines, and you’d see different beliefs. People defending aristocratic city states like the Hanseatic League, people defending Catholic monarchy, the people defending a proto-absolutist, nationalist model. And today you hold a party and you bring in

people from Bangkok and New York City and London, and all of them have dark jackets and bow ties, all of them eat the same food, speak the same language, and they have the same beliefs and; democracy, majority rule, progress.

DF: On the other hand, one of the virtues of a world civilisation is that a minority of 1% is still a very large number of people. So that one of the things that you get with the kind of world civilization that the internet gives you is lots and lots of relatively small groups which can identify with each other. So I’m not sure that what I’m calling a world civilization necessarily means a uniform world civilization. It’s uniform in the sense that everybody on the internet almost speaks English, or at least can read and write English, but I don’t think it’s uniform in the sense that they necessarily have the same beliefs.

It’d be interesting to know whether small heretical religious groups, people like the Mormons, the original Mormons, and the Seventh Day Adventists and things like that, have become more or less common over the last century. And I just don’t know.

SF: I’ll end by inviting a degree of hope, hopefully. How optimistic are you about the future of liberty?

DF: Globally, I’m naturally an optimist, but as a theorist, I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist. But I think generally, things are going in all directions at once. I mean, it’s true even of Trump, that there is the optimistic view, which is that his attempt to reduce the size of government is going to matter, and that the Department of Education is going to get abolished, which would be a fine thing, and a bunch of other things, and that the tariffs will be a flash in the pan and and his his attempt to kick all of the illegal immigrants out of the US is going to eventually clog up, because there are just too many people, and you can’t do it.

That would be the optimistic view, that the good parts of what he’s doing will survive and the bad parts won’t. And the pessimistic view is the other way around. And then the two other pessimistic views are the view that Tom Palmer has, which is that Trump will, in effect, succeed in establishing a dictatorship in the US, which I think is quite unlikely, but I could be wrong, and the view in the other direction, which is the Trump will make himself so unpopular, Democrats will come back with even more votes, and we will get even more increase in size of government and government regulation and so forth. So there are there optimistic and pessimistic futures, and I can’t judge among them.

SF: I suppose we might end on that note. Thank you so very much for giving us your time!