Vienna, 2026.

Outside, the city is orderly. Inside, in a high-ceilinged apartment with parquet floors and shelves bending under the weight of treatises on value and human action, four men sit around a low table. There is red wine. There are heart-shaped chocolates, purchased ironically and consumed sincerely.

Carl Menger adjusts his spectacles. Ludwig von Mises holds the remote as if it were a moral instrument. Friedrich Hayek sits slightly apart, already skeptical of any central narrative. Murray Rothbard is grinning, delighted that romance might yet be weaponized against social planning.

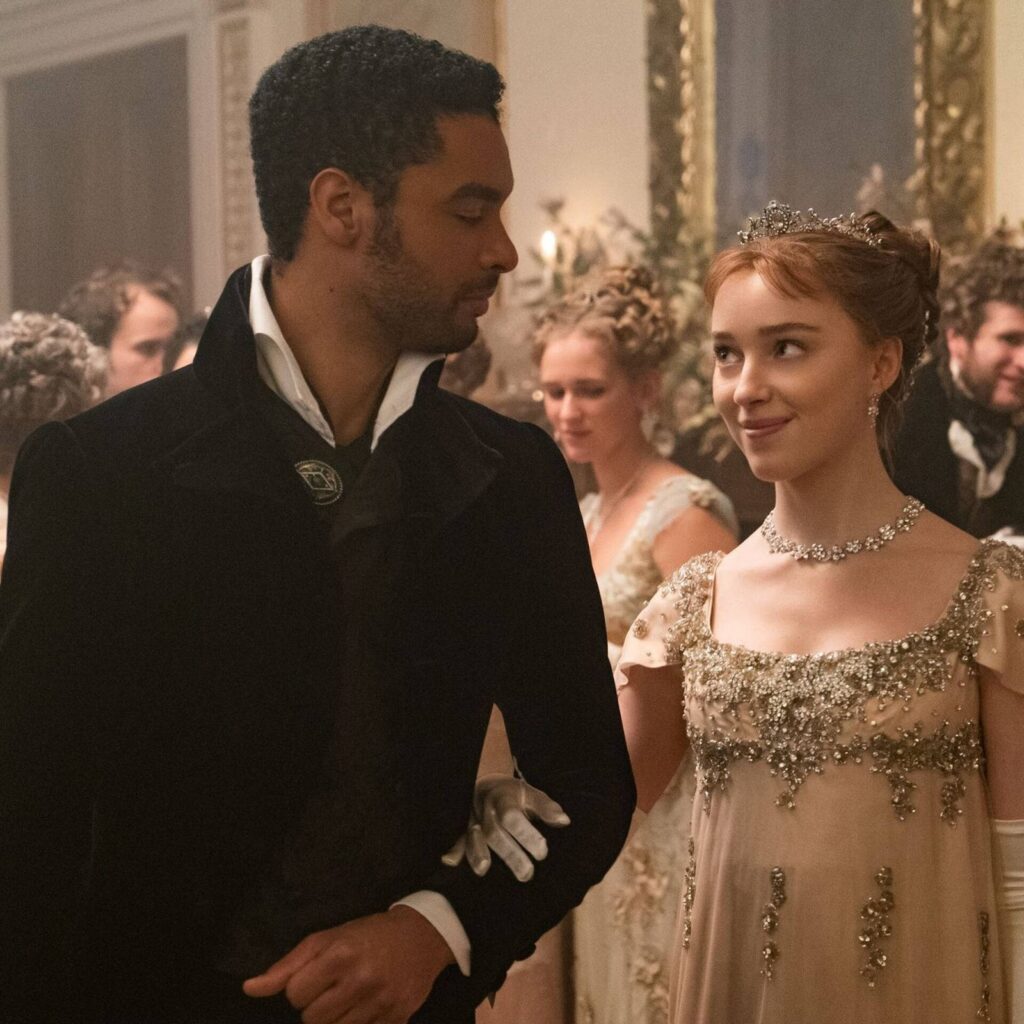

On the screen: Regency London, 1813 – Bridgerton

To understand what they are watching, one must first understand the market. The marriage market is not a metaphor here. It is an institution. Young women are “presented.” Young men are evaluated. Rank, wealth, lineage, and reputation determine one’s apparent “price.” The Queen may anoint a debutante “the diamond,” inflating her demand overnight. Mothers operate as regulators. Gossip functions as enforcement. Deviations are punished socially.

It looks like silk and violins. It behaves like a centrally influenced, reputation-driven exchange under moral surveillance.

And into this choreography steps the Bridgerton family: eight siblings, raised in affection, wealth, and relative freedom, yet subject to the same public valuation. They are prime assets in a constrained system. And each one disrupts it.

Anthony Bridgerton: The Reluctant Central Planner of His Own Heart

Anthony is the eldest son. At eighteen, he watches his father collapse and die from a bee sting. In a single afternoon, he becomes Viscount. He inherits land, title, income, obligations, and the unspoken expectation that he must be unbreakable. He becomes not merely a brother but the executive authority of the Bridgerton enterprise, as he is grieved by his mother, watched in jealousy by his siblings, and the weight of the estate gets placed on his shoulders.

Anthony internalizes a principle that no Austrian would endorse, but every traumatized heir understands: risk must be minimized. He resolves not to marry for love, as in his mind, it wasn’t just the bee sting that killed his father—it was the love his mother bore for him that destroyed the family they knew.

To the young Anthony, the trauma was cemented not by the funeral but by the sight of his mother collapsing into a grief so total it rendered her a ghost. He saw love as the ultimate liability, a force capable of inducing a complete systemic collapse of the person. If love is what broke his mother, he decides, then love is a variable he must eliminate from his own balance sheet to ensure the Bridgerton enterprise remains standing.

Mises leans forward. “Here is a man who equates love with extreme volatility. He views his mother’s grief as a total emotional bankruptcy. To protect the estate, he believes he must legislate against the very feeling that caused the crash.”

He sets out to select a wife the way one selects a stable bond: seeking out a compatible, reputable, sensible maiden. He chooses Edwina Sharma, the season’s other star, whose virtues are visible and her reputation intact.

And then he meets Kate Sharma.

Kate is Edwina’s older sister. Intelligent, sharp-tongued, fiercely protective. She has sacrificed her own marital prospects to secure her sister’s future. She understands duty as intimately as Anthony does.

Hayek speaks softly. “He attempts to design his life from above. She embodies the limits of his design.”

Kate does not defer. She challenges him. She mirrors his pride and his restraint. She refuses to be managed.

Anthony’s choice, when it comes, is not efficient. It is not reputationally optimal. It is not risk-minimizing. It is, in Austrian terms, revelatory.

His revealed preference contradicts his stated strategy. He does not value predictability above all. He values recognition. He values being seen by someone who understands the cost of responsibility. He values an equal.

Rothbard raises his glass. “He abandons planned equilibrium for spontaneous order.”

Anthony’s love is not irrational. It is the expression of a deeper ranking of values: intensity, parity, shared burden over tranquil appearance.

Daphne Bridgerton: The Diamond Who Refuses to Be Priced

Daphne is the fourth child but the eldest daughter. When she enters society, she is declared “the diamond of the season” by the Queen. In one sentence, her market value soars. Invitations multiply. Suitors circle.

From a distance, she appears perfectly positioned. She is kind, beautiful, musically inclined, and socially adept. She desires marriage and children, not rebellion.

Yet her early prospects disappoint. The men who approach her perform interest rather than embody it. They admire her as a trophy.

Enter Simon Basset, Duke of Hastings.

Simon is wealthy, powerful, and emotionally scarred. Raised by a father who despised weakness, he grew up with a speech impediment that invited cruelty. He swore never to marry, never to produce an heir, as an act of defiance against his lineage.

Daphne and Simon begin with a ruse. They pretend to court in order to manipulate public perception. He gains freedom from matchmaking pressure. She gains desirability through association.

Menger smiles. “Observe how price signals distort perception.”

The fake courtship functions as a signaling device. Demand rises, reputation shifts, and the market reacts to appearances.

But the deeper drama unfolds in private. Daphne sees Simon’s wound. She intuits that beneath his vow lies pain, not indifference.

Why does she choose him, knowing he rejects children, when her own highest aspiration is motherhood?

Mises answers quietly. “Because she values the man more than the contract.”

Her decision is not naive. It is evaluative. She ranks emotional depth and the possibility of healing above immediate certainty. She is not seduced by the title; she already possesses status. She seeks transformation.

Daphne’s love is entrepreneurial in a moral sense. She invests in a future that does not yet exist. She believes value can be created within relationship.

The Austrians do not call this sacrifice. They call it preference.

Colin Bridgerton: The Problem of Self-Knowledge

Colin is charming, amiable, restless. The third son, he bears no crushing responsibility. Yet that freedom breeds insecurity. Without a defined role, he seeks meaning through travel, stories, ambition.

He wants to be taken seriously, amid fears that he is ornamental.

Penelope Featherington, his longtime friend, stands at the margins of every ballroom. Overlooked, underestimated, dressed in unfashionable colors, she is assumed to be minor.

In secret, she is Lady Whistledown, the anonymous author of society’s most influential gossip sheet. She controls information. She shapes reputations. She understands everyone.

Hayek’s eyes light up. “Distributed knowledge.”

Penelope holds local, tacit knowledge of Colin’s character. She has observed him for years. She sees his kindness and his vanity, his longing and his immaturity.

Colin fails to perceive her for much of the series. He absorbs the market’s assessment of her low value.When he finally recognizes her worth, it is not because her price has risen. It is because his perception has matured.He chooses the one person who knows him unmarketed. With Penelope, he is not a brand, but an individual.

Rothbard laughs. “He defects from public valuation to private assessment.”

Colin’s love is a movement from self-display to self-knowledge.

Eloise Bridgerton: The Refusal of Commodification

Eloise enters no ballroom with enthusiasm. She questions the institution itself. Why must women marry? Why is intellect ornamental? Why is the market structured as if female worth culminates in alliance?

She reads radical pamphlets. She resents debut rituals. She views marriage as potential confinement.

In economic terms, she challenges the framework of exchange.

Menger nods with approval. “Her ranking places autonomy above approval.”

Eloise does not experience desire through spectacle. She is drawn, when she is drawn at all, to conversation, to ideas, to rebellion. Her attachment to Theo Sharpe, a printer’s assistant, emerges not from status but from discourse. He introduces her to political thought beyond her class.

The relationship is socially dangerous. It threatens her reputation. It violates hierarchy.

Hayek remarks, “No central authority can calculate the value of intellectual companionship.”

Eloise’s selectivity is not arrogance, but coherence. She refuses to exchange herself under terms she did not consent to design.

If Anthony is authority and Colin is identity-in-progress, Benedict is something more dangerous: he is aesthetic freedom embodied. Possibly the most attractive sibling, not merely in physical terms but in existential ones, he carries that rare combination of beauty, detachment, and refusal to be instrumentalized. He is not simply desirable. He is unclassifiable.

Carl Menger leans forward. “Observe,” he says, “a man who does not derive value from assigned rank.”

Benedict is the second son. That matters more than it seems.

He does not carry the crushing responsibility of inheritance like Anthony. He is not expected to secure the family’s financial continuity. Nor is he socially invisible. He exists in a liminal space, economically buffered, socially respected, structurally unnecessary. And that kind of freedom can be destabilizing.

Without the pressure of title, he is not forced into early marriage negotiations. Without the anxiety of irrelevance, he is not compelled to define himself through productivity. So he turns toward art. Toward aesthetic experience. Toward salons, studios, and bohemian gatherings where hierarchy dissolves into experimentation.

Mises watches carefully. “He is testing alternative value systems.”

Benedict moves in spaces where class lines blur, where pleasure is exploratory, where identity is not policed by debut rituals. He is not rebelling in the theatrical sense. He is sampling different modes of being.

Benedict’s bisexuality is not a sensational subplot. It is philosophically coherent with Austrian theory. In a society that rigidly categorizes desire, he reveals a preference structure that refuses binary constraints.

He is drawn to people, not to roles.

Menger would phrase it plainly: value is not inherent in a category. It is assigned by the evaluator. Benedict does not rank partners based on socially prescribed utility. He ranks based on intensity, aesthetic charge, and authenticity of encounter.

In economic language, he ignores price signals in favor of direct valuation.

In a highly regulated marriage market like 1813 London, this is subversive. If the system relies on predictable sorting, then fluid desire destabilizes it.

Rothbard smiles. “A man who will not let the state of convention regulate his attraction.”

Benedict’s artistic aspirations are not decorative, but existential. He fears that his acceptance into art school may have been purchased by his family’s name rather than earned by merit, a suspicion that eats at him.

He wants something real, not inherited prestige, nor subsidized credibility.

Hayek interjects. “He is searching for spontaneous order within himself.”

Art becomes his laboratory for authenticity. Through creation, he seeks evidence that his value is intrinsic, not conferred.

And this search mirrors his romantic life. He cannot tolerate relationships that feel transactional. He recoils from courtships structured around alliance and advantage. He gravitates toward encounters that feel unmediated, unpriced.

When Benedict meets Sophie at a masquerade ball, he does not know her status. She appears as a mysterious woman in silver. He is captivated not by lineage but by presence. He falls in love without market data.

Later, he discovers that Sophie is socially inferior, effectively a servant. In a system obsessed with rank, this revelation should trigger recalculation, yet it does not.

Mises speaks quietly. “His preference ranking was formed prior to price revelation.”

He loved the individual encountered, not the classification assigned. Once the state of the world changes, his valuation does not collapse. It remains anchored in experience, not in status.

This is pure subjective value theory in action. The market may reprice Sophie. Benedict does not.

If Eloise is the intellectual revolutionary, Benedict is the sensual one. They form an unspoken alliance within the family. Eloise resists the marriage market on ideological grounds. She questions the structure, the gender constraints, the commodification of women. Her rebellion is discursive. Benedict resists through lived practice. He simply refuses to internalize the logic of the market. He does not argue against it as forcefully. He sidesteps it.

Hayek would note the distinction: Eloise challenges the system explicitly. Benedict erodes it implicitly.

Both Eloise and Benedict reject the assumption that family duty must define desire. They seek a version of intimacy not reducible to a social alliance. But where Eloise demands intellectual parity, Benedict seeks aesthetic resonance. He wants to be undone slightly—to encounter a person or a truth so powerful that his social armor fails, leaving him changed.

Part of Benedict’s allure lies in unpredictability. In a ballroom full of men performing eligibility, he performs curiosity. In a culture that rewards conformity, he rewards strangeness.

Attractiveness, in Austrian terms, is not a measurable asset. It is a subjective reaction to perceived autonomy and depth.

He is attractive because he does not seem to need validation from the market.

Rothbard finishes his wine. “Nothing is more destabilising than a man who refuses to convert himself into currency.”

What the Austrians Conclude

By the end of the binge, the economists agree on one point.

Anthony teaches us about risk and revealed preference.

Daphne teaches us about investment in potential.

Colin teaches us about information asymmetry and self-knowledge.

Eloise teaches us about autonomy under constraint.

Benedict teaches us something subtler. He demonstrates that when value is truly subjective, it will not align neatly with social hierarchy, gender expectations, or inherited structure. He embodies the Austrian insight that preference cannot be centrally planned.

In a world that assigns price tags to people, Benedict chooses as if price were irrelevant.

And that, in any century, is radical.